CLOSING

THE

DIGITAL

SKILL

DIVIDE

FEBRUARY 2023

THE PAYOFF FOR

WORKERS, BUSINESS,

AND THE ECONOMY

By Amanda Bergson-Shilcock

and Roderick Taylor

with Nye Hodge

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This report was written by Amanda Bergson-Shilcock and Roderick Taylor of National Skills Coalition

with data analysis by Nye Hodge, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta. The report team included Jeannine

LaPrad and Rachel Unruh of National Skills Coalition and Sarah Miller, Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta.

The opinions expressed in this report reflect those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of

the Federal Reserve System or the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta.

About National Skills Coalition: Jobs that require skills training are the backbone of our economy.

National Skills Coalition fights for a national commitment to inclusive, high-quality skills training so

that more people have access to a better life, and more local businesses see sustained growth. Since

2000, through expert analysis and technical assistance, broad-based organizing, targeted advocacy, and

cutting-edge communications, NSC has changed hundreds of state and federal skills policies that have

changed thousands of lives and grown local businesses and economies.

About the Center for Workforce and Economic Opportunity at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta:

The Center for Workforce and Economic Opportunity focuses on employment policies and labor mar-

ket issues that affect low- and moderate-income individuals. It acts as a bridge between research and

practice, connecting researchers, businesses, and policymakers with innovative approaches to creating

economic opportunity through education and employment. The center also contributes to economic

research and monetary policy discussions by tracking labor market trends affecting low- and moder-

ate-income workers.

CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY 1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................. 3

CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE ..................................... 7

Missing from the digital divide discussion: Skills ...................... 8

Almost all jobs now require digital skills ..................................... 9

Not just a silicon valley problem: The digital skill

divide spans every industry and firm size .................................. 13

Inequities within the digital skill divide........................................ 14

The payoff of closing the digital skill divide ............................... 15

RECOMMENDATIONS .................................................................. 18

ENDNOTES .................................................................................... 20

APPENDIX ..................................................................................... 23

State Profile: North Carolina ....................................................... 25

State Profile: Illinois ....................................................................... 38

METHODOLOGY ............................................................................ 52

CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY 1

NOW — AS LEADERS DESIGN

LABOR MARKET POLICIES

TO DRIVE A THRIVING AND

INCLUSIVE ECONOMY — IT IS

IMPERATIVE TO UNDERSTAND

THIS ACCELERATION OF

DIGITAL TRANSFORMATION.

2 CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY 3

EXECUTIVE

SUMMARY

E

ven before the coronavirus pandem-

ic began, policymakers, business-

es, and workforce advocates were

already recognizing that workers

were not being replaced by robots, but rather,

being called upon to work hand-in-glove with

rapidly evolving technology.

When the pandemic struck, millions of U.S.

companies hustled to change how they did

business. Nearly every worker suddenly had

to contend with new digital demands — even

those in frontline, essential roles. The im

-

pact of the digital skill divide became more

acute, weighing disproportionately on work

-

ers of color and smaller businesses strug-

gling to survive a tumultuous economy.

Now — as leaders design labor market poli

-

cies to drive a thriving and inclusive econ-

omy — it is imperative to understand this

digital transformation. This report takes

a first-ever look at the demand for digital

skills in the U.S. economy, as measured by

a dataset of 43 million “Help Wanted” ads

posted during 2021.

1

The opinions expressed in this report reflect those of the

authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Federal

Reserve System or the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta.

A note about terminology:

This report uses digital

skills and technology

skills interchangeably.

2 CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY 3

The findings in this analysis are unequivocal:

■

There is overwhelming demand for digital skills

in the labor market, with 92 percent of all job ads

requiring definitely digital or likely digital

2

skills.

This demand is robust across all industries, and

small businesses are just as likely as their larger

peers to seek workers with technology skills.

■

Yet many workers have not had sufficient oppor-

tunity to build such skills; earlier research found

that nearly one-third of U.S. workers do not have

foundational digital skills, and workers of color fall

disproportionately into this category due to struc-

tural inequities.

3

■

Equipping workers with necessary skills requires

action by both private employers and public policy-

makers. Notably, public investments in workforce

development and education are especially vital

given the unevenness of private investments and the

prevalence of digital skill demands among smaller

businesses, which depend on publicly funded work-

force and education partners to upskill employees.

■

Closing the digital skill divide has major payoffs for

businesses. Prior research has shown that workers

value upskilling opportunities and prefer working

for employers who offer clear, well-defined path-

ways to advancement.

4

Because turnover has heavy

costs for businesses – with estimates ranging from

$25,000 for workers who leave within the first year

to over $78,000 for workers who leave after five

years,

5

averting or delaying turnover by ensuring

that workers have upskilling opportunities can be

economically significant.

■

Public investments in closing the digital skill divide

can also generate economic benefits for individ-

ual workers and the broader economy. People

who qualify for jobs that require even one digital

skill can earn an average of 23 percent more than

those working in jobs requiring no digital skills —

an increase of $8,000 per year for an individual

worker.

6

These increased earnings could result in

more state and federal tax revenue generated by

each worker. Depending on the household size and

composition, this could range from $1,363 to $2,879

per year.

7

SKILLS HAVE BEEN MISSING FROM

THE DIGITAL DIVIDE CONVERSATION

Vivid news stories of the “homework gap” have helped

drive public awareness and urgency around access to

broadband and high-quality devices. But, while the dig-

ital access divide has gotten high-profile coverage, the

digital skill divide has not.

Awareness of the digital skill divide began to grow with

passage of the $2.75 billion Digital Equity Act

8

as part

of the 2021 federal infrastructure law. This funding will

help people build digital skills as well as obtain access

to broadband and devices, and will help states to close

equity gaps among key populations, including people

of color, low-income individuals, veterans, and rural

residents.

ACROSS

INDUSTRIES,

92%

OF JOBS

REQUIRE DIGITAL

SKILLS

47%

definitely require

digital skills

8%

do not require

digital skills

45%

likely require

digital skills

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

4 CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY 5

RECOMMENDATIONS

Ensuring that public investments are intentionally

focused to remedy the digital skill divide and related

inequities is vital to U.S. economic success.

9

As the fed-

eral Digital Equity Act is implemented in states, policy-

makers will have a powerful opportunity to close gaps in

racial, gender, age and geographic equity. Similarly, as

officials work to update landmark policies such as the

Workforce Innovation and Opportunity Act (WIOA), it is

crucial to incorporate the latest findings on how to close

the digital skill divide.

Building on the findings laid out in this report, there

are three overarching principles to guide leaders’

decisionmaking:

1. A digital skill foundation for all.

All workers need the opportunity to develop broad-

based, flexible digital problem-solving skills for current

technologies and ongoing technological shifts.

■

Policymakers can support this goal by investing in

free or low-cost digital skills training for workers, and

ensuring that workforce development and education

providers are equipped to provide high-quality upskill-

ing programs.

■

Workforce and education advocates and providers

can support this goal by speaking up for digital equity

investments that support workers’ goals and aspira-

tions and respond to local businesses’ skill needs.

■

Corporate decisionmakers and influencers can use

their platforms to ensure that skills are central to digi-

tal divide discussions in the public and policymaking

spheres.

2. Ongoing upskilling for every worker in every

workplace.

Workers in every industry need the opportunity to

develop industry- and occupation-specific digital skills to

adapt and advance in their careers.

■

Policymakers can support this goal by investing in

industry sector partnerships

10

that can collaborate

with community colleges and other training providers

to ensure that the talent development process is con-

nected to industry-specific skill needs and jobs.

■

Workforce and education advocates and providers

can encourage policymakers to embed digital prob-

lem-solving skills as allowable or required activities

under existing workforce development, adult educa-

tion, and higher education policies, as well as digital

equity policies.

11

■

Corporate decisionmakers and influencers can

implement policies and practices that support digital

upskilling for workers at every level of their organiza-

tions. Smaller businesses can participate in regional

industry partnerships that support these efforts

across small businesses at scale.

3. Rapid reskilling for rapid re-employment.

We need to be ready for sudden disruptions to the labor

market or specific industries. Policies should support

rapid reskilling so workers can move from one industry

to another.

■

Policymakers can support this goal by supporting

access to skills for workers who have lost their jobs,

including those transitioning to a new industry. This

includes ensuring that student financial aid policies

match the reality of how digital skills are acquired.

■

Workforce and education advocates and

providers can support this goal by sharing their

expertise with policymakers on topics such as best

practices in closing racial equity gaps in digital

skill-building opportunities.

■

Influencers and corporate decisionmakers can

educate state and federal policymakers about the

skills mismatches they are experiencing and the

kinds of technology skills their companies need to

be successful.

CONCLUSION

Despite the high demand for digital skills and the desire

for skill building opportunities among workers, many

have not had the opportunity to fully develop such

skills.

12

These burdens fall unequally on workers and

entrepreneurs of color. Investing in digital skill-building

can help individual workers increase their incomes,

allow businesses to thrive, and create positive eco-

nomic spillover effects for local, state, and national

economies.

This report puts actionable data into the hands of

elected officials, education and training providers, and

corporate decisionmakers, allowing them to fully tackle

the skills aspect of the digital divide.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

4 CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY 5

WHAT IS A DIGITAL SKILL?

Some digital skills are foundational

skills such as email, simple spread-

sheets, data entry, or timecard soft-

ware. Others are industry-specific

skills, such as bookkeepers using

QuickBooks, manufacturing workers

using AutoCAD, or home health aides

using electronic medical records.

WHAT IS THE

DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE?

The digital skill divide is the space

between those who have the robust

access and support needed to engage

in skill-building opportunities and those

who do not. As technology evolves, the

digital skill divide prevents equal par-

ticipation and opportunity in all parts

of life – including people’s ability to get

good jobs and advance in a career.

13

6 CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY 7

E

ven before the coronavirus pandemic struck

in 2020, policymakers, businesses, and work-

force advocates were already recognizing that

workers were not being replaced by robots, but

rather, being called upon to work hand-in-glove with

rapidly evolving technology.

This new awareness brought home the importance of

developing digital resilience,

14

which equips workers and

businesses to continuously adapt to changing technolo-

gies. At the same time, it spotlighted the stark economic

costs caused by uneven investment in people’s skills and

new technologies — namely, decreased financial security

and career opportunities for workers themselves, and

reduced productivity for firms.

15

A growing understanding of this digital skill divide also

illuminated how the ripple effects of historical policies

and structural racism continue to contribute to mod-

ern-day inequities in digital skills and access,

16

and the

vital role of public policy and practice in remedying

inequities caused by prior policies.

17

When the pandemic struck, millions of businesses hus-

tled to change how they served their customers. Nearly

every worker suddenly had to contend with new digital

demands — even those in frontline, essential roles. The

impact of the digital skill divide became more acute,

weighing disproportionately on some workers — includ-

ing workers of color and low-wage workers — and smaller

businesses struggling to survive a tumultuous economy.

Now — as leaders design labor market policies to drive

a thriving and inclusive economy — it is imperative to

understand this acceleration of digital transformation.

The findings in this analysis are unequivocal: policymak-

ers, business leaders, workforce advocates, educators,

and training providers who gain perspective on this

transformation and its impact on the digital skill divide

(including population inequities within that divide), will

be well-positioned to reap the economic payoff of clos-

ing the divide.

Key findings include:

■

There is overwhelming demand for digital skills in the

labor market, with 92 percent of all job ads requiring

definitely digital or likely digital skills. This demand

is robust across all industries, and holds true even for

entry-level jobs that require zero to two years of expe-

rience or a high school diploma. And small businesses

are just as likely as their larger peers to seek workers

with technology skills.

■

Yet, many workers have not had sufficient oppor-

tunity to build such skills; earlier research found

that nearly one-third of U.S. workers do not have

foundational digital skills, and workers of color fall

disproportionately into this category due to structural

inequities.

18

■

Equipping workers with necessary skills requires action

by both private employers and public policymakers.

Notably, public investments in workforce develop-

ment and education are especially vital given the

unevenness of private investments and the prevalence

of digital skill demands among smaller businesses.

Small businesses employ 47 percent of private-sector

workers

19

and rely more heavily on publicly funded

CLOSING THE

DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE

THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS,

AND THE ECONOMY

ACROSS

INDUSTRIES,

92%

OF JOBS

REQUIRE DIGITAL

SKILLS

47%

definitely require

digital skills

8%

do not require

digital skills

45%

likely require

digital skills

6 CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY 7

workforce development and education partners

(rather than in-house programs) to upskill employees.

■

Closing the digital skill divide has major payoffs for

businesses. Prior research has shown that workers

value upskilling opportunities and prefer working for

employers who offer clear, well-defined pathways

to advancement.

20

Because turnover has heavy

costs for businesses — with estimates ranging from

$25,000 for workers who leave within the first year

to over $78,000 for workers who leave after five

years,

21

averting or delaying turnover by ensuring

that workers have upskilling opportunities can be

economically significant.

■

Public investments in closing the digital skill divide

can also generate economic benefits for individual

HOW THIS REPORT WAS PRODUCED

To produce this report, the research team analyzed

43 million online job postings published in 2021 and

collected by Lightcast (formerly known as Emsi

Burning Glass). The dataset assembled by Lightcast

included information on the particular skills associ-

ated with each job posting.

The typical job ad required applicants to have 8

different skills. Across all ads, there were 15,000

distinct skills extracted and standardized by

Lightcast from the universe of 2021 job ads. The

authors of this report manually coded the top

50 percent of these skills — that is, the 7,500

skills that were most often requested in job ads.

(Notably, however, this top 50 percent accounted

for 99.99 percent of job ads, while the remaining

uncoded skills only accounted for .01 percent of

jobs.) This coding formed the basis for the original

analysis and findings in this report.

The research team coded each skill according to

whether it was definitely digital, likely digital, or

not digital. Knowledge of Salesforce software or

the Python programming language were coded

as definitely digital. An example of a likely digital

skill would be survey design or bookkeeping —

tasks that today are frequently accomplished

with the use of a computer or other digital device,

but could still be carried out in an old-fashioned

analog fashion. An example of a not digital skill is

changing diapers.

Further information is available in the

Methodology section at the end of this report.

workers and the broader economy. People who

qualify for jobs that require even one digital skill

can earn an average of 23 percent more than

those working in jobs requiring no digital skills —

an increase of $8,000 per year for an individual

worker.

22

These increased earnings could result in

more state and federal tax revenue generated by

each worker. Depending on the household size and

composition, this could range from $1,363 to $2,879

per year.

23

MISSING FROM THE DIGITAL DIVIDE

DISCUSSION: SKILLS

The time is ripe for an analysis of this issue. In the past

few years, vivid news stories of the “homework gap”

coupled with images of people — often low-income fami-

lies of color — trying to access wifi from parking lots and

other makeshift setups have helped drive public aware-

ness and urgency around solving the digital divide.

Policymakers at all levels of government have responded

with initiatives to help individuals and businesses access

high-speed internet, obtain digital devices, and otherwise

equip themselves for full participation in today’s increas-

ingly digital society. Corporate leaders, philanthropists,

educators, and worker advocates have been equally

motivated to tackle these widespread challenges.

But, while the digital access divide has gotten high-pro-

file coverage, the digital skill divide has a much lower

profile. This has only recently begun to change with pas-

sage of the federal Digital Equity Act as part of the land-

mark Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act in 2021.

For the first time, Congress invested $2.75 billion in state

and local efforts to help people build digital skills as well

as obtain access to broadband and devices. Importantly,

this legislation identifies a number of “covered popula-

tions” — including people of color, low-income individ-

uals, rural residents, and veterans, among others — for

whom states must specifically work to close equity gaps

in digital access and skills.

24

As implementation of the new law begins, stakeholders

have a unique opportunity to build on the momentum

of this trailblazing legislation, while also identifying the

additional resources needed to fully address workers’

and businesses’ digital skill needs. This report puts

actionable data into the hands of elected officials,

education and training providers, and corporate

decisionmakers, positioning them to tackle the skills

aspect of the digital divide.

8 CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY 9

ALMOST ALL JOBS NOW REQUIRE

DIGITAL SKILLS

The overwhelming majority of jobs in the U.S. labor

market now require technology skills. Fully 92 percent

of the forty-three million online job ads analyzed for

this study are seeking workers who have at least one

definitely digital or likely digital skill. More specifically,

nearly half (47 percent) of all job ads list at least one

skill that is definitely digital — that is, requiring job

applicants to be able to use a software program like

AutoCAD or QuickBooks. Another 45 percent of all

job ads list at least one skill that likely requires digital

capability, such as customer account review, making

travel arrangements, or clerical support.

This high demand for technologically skilled workers is

reflected across each of the fifty states, the District of

Columbia, and Puerto Rico. Hawaii and Alaska are at

the high end of the spectrum, with 93 percent of job

postings in both states requiring workers with definitely

digital or likely digital skills.

25

But even the state at the

bottom of the list, Montana, still shows a robust 88 per-

cent of all job ads seeking workers with definitely digital

or likely digital skills.

This demand for technology skills stretches across every

industry in the U.S., and nearly every occupation, includ-

ing entry-level and frontline workers. Gone are the days

when only software engineers or white collar workers

needed digital skills. Today, job ads seeking janitors, food

service workers, and agricultural workers also cite the

need for digital skills.

The importance of workers having a baseline of founda-

tional digital skills and experience with widely used soft-

ware products is illustrated by their appearance as some

of the most requested skills across all forty-three million

job postings. Indeed, across all 15,000 skills captured

in this dataset, Microsoft Excel was the ninth most

requested skill, mentioned in more than 4.9 million

postings, and the general skill of computer literacy was

thirteenth on the list.

Even entry-level jobs increasingly demand

digital skills.

Among job ads seeking workers with zero to two years of

experience — primarily new entrants to the workforce

26

— fully 95 percent of ads required a definitely digital

or likely digital skill. The numbers were only just barely

higher for workers with more experience. (See Figure 1.)

However, there was a difference within the subset of

ads requiring a definitely digital skill. Nearly half (49

percent) of jobs seeking entry-level workers with zero to

two years of experience included a definitely digital skill.

The number leapt to more than two-thirds (71 percent)

of ads for workers with three to five years of experience.

(Also shown in Figure 1.)

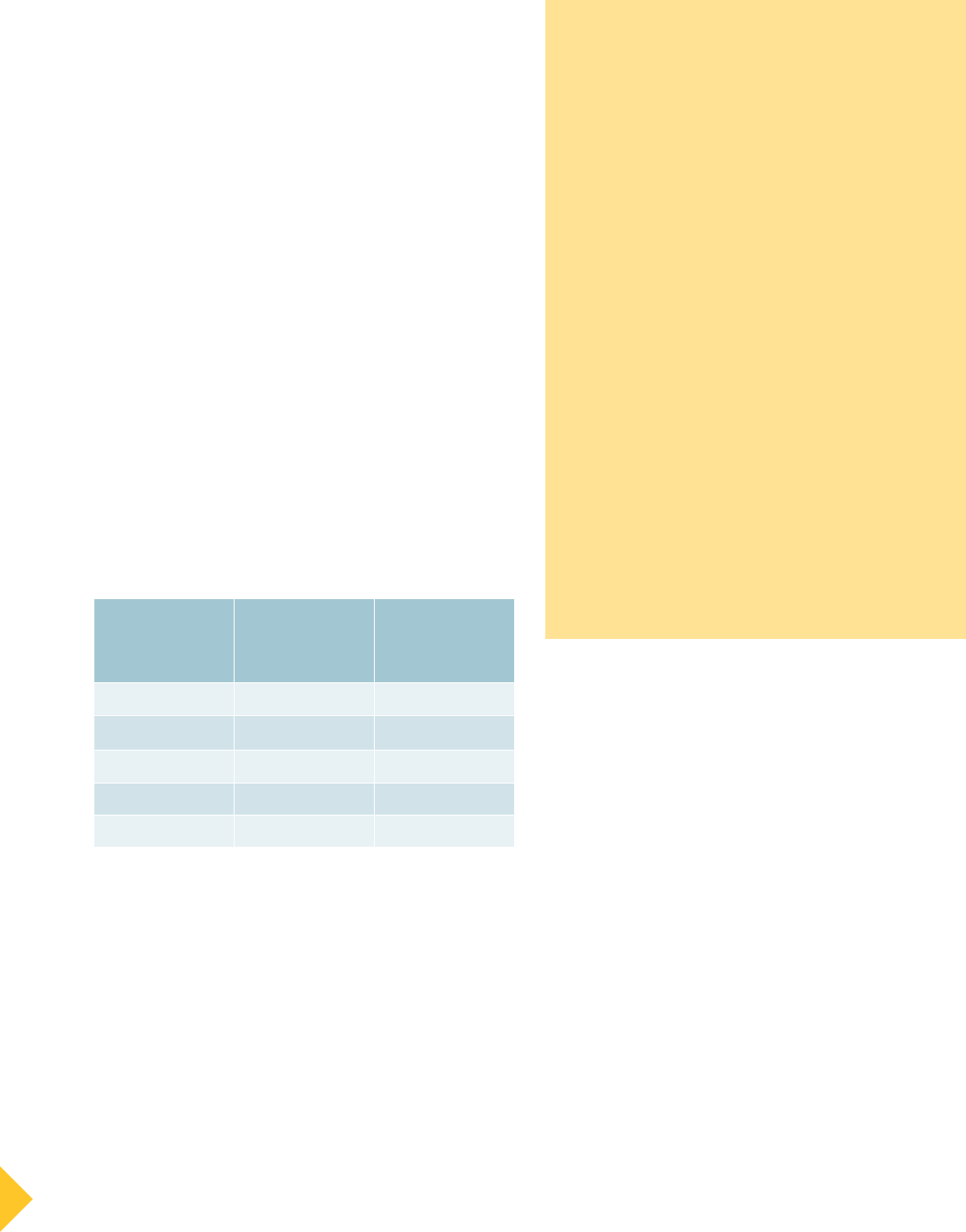

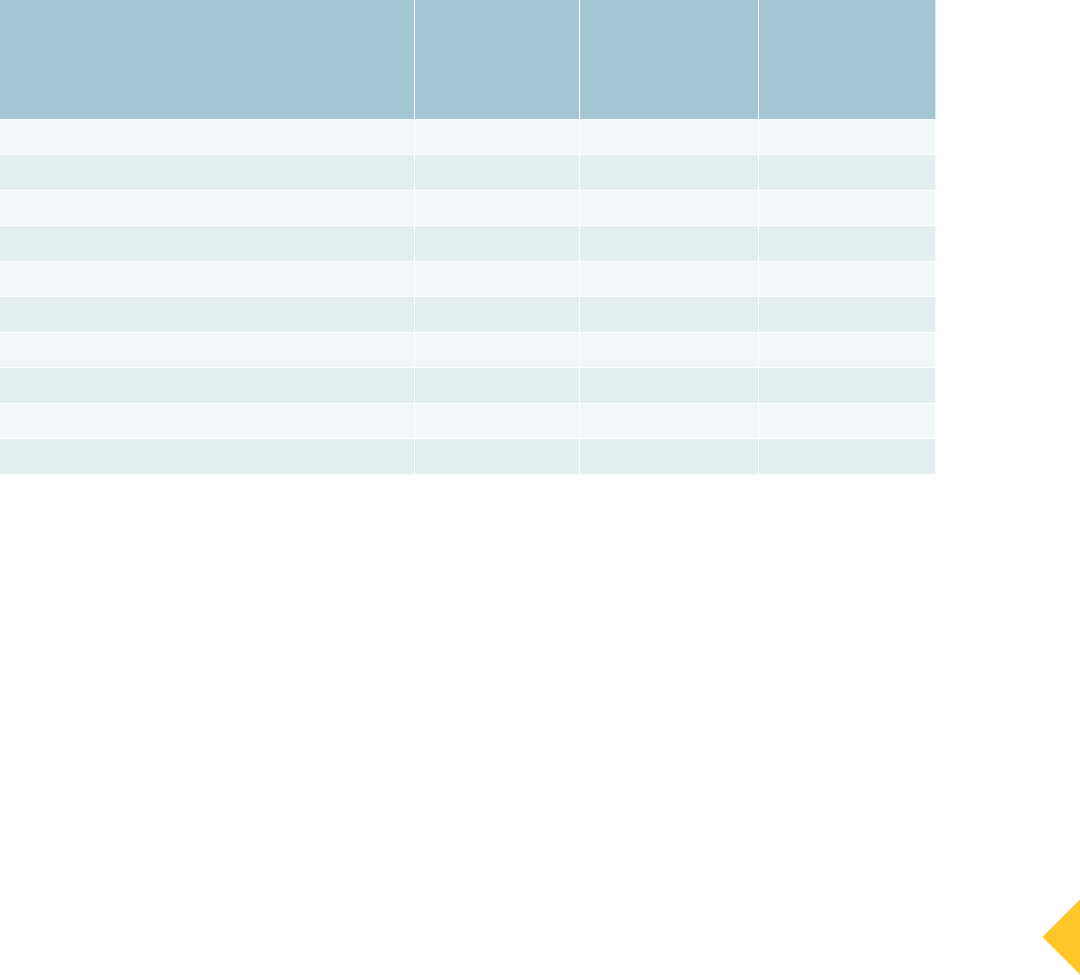

FIGURE 1: Digital skills are in high demand in job ads

for entry-level workers (2021)

2021 job ads

seeking:

Percentage of ads

requiring a likely

digital skill:

Percentage of ads

requiring a definitely

digital skill:

0-2 years of

experience

95% 49%

3-5 years 98% 71%

6-8 years 99% 81%

9+ years 98% 75%

Note: Because not all job ads include a “years of experience” require-

ment, this finding reflects the universe of the 20 million job postings for

which Lightcast was able to discern such a requirement

8 CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY 9

Some occupations have especially fast growing

demand for digital skills.

While some occupations show slow but steady growth

in the percentage of job ads that require digital skills,

other occupations have shown a much quicker increase.

For example, in 2019 just 15 percent of ads for oilfield/

rig worker required a definitely digital skill. But just

two years later, in 2021, that number had risen to 38

percent. Other jobs with rapid increases included diesel

mechanic, community health worker, tool and die maker,

and loss prevention/asset protection specialist. These

examples show how rapidly the landscape is changing in

certain segments of the labor market.

Even jobs that require limited education still

demand digital skills.

Even positions that require workers to have relatively

less education are still overwhelmingly likely to require

digital skills. Fully 94 percent of job ads that require

applicants to have a high school diploma or equivalent

include at least one skill that is definitely digital or likely

digital. This number rises slightly for job ads requiring

higher-level educational credentials. (See Figure 2.)

FIGURE 2: Digital skills are required for workers

regardless of their educational level (2021)

27

Education level

required

Percentage of

ads requiring a

likely digital skill

Percentage of

ads requiring

a definitely

digital skill

High School 94% 46%

Associate’s 97% 47%

Bachelor’s 99% 74%

Master’s 97% 46%

PhD 97% 39%

Findings are similar among the subset of jobs that

require at least one definitely digital skill. Forty-six

percent of jobs requiring a high school diploma request

such skills, as do forty-seven percent of jobs requiring an

associate’s degree.

SURPRISING BUT TRUE: YOUNGER

WORKERS NEED DIGITAL SKILLS TOO.

While it is often assumed that younger workers

are so-called “digital natives” who automatically

know how to use technology, research shows this

is often not the case. An earlier study by NSC

found that fully 25 percent of workers with no

foundational digital skills and 29 percent of those

with very limited foundational skills were between

the ages of sixteen to thirty-four.

28

One reason behind this phenomenon is that

younger workers — like their older peers — often

have fragmented knowledge. That is, they are

comfortable with some digital tasks, such as

sending a text message or making a TikTok video,

but not comfortable with others, such as creat-

ing a spreadsheet. For this reason, it’s especially

important that workforce and education programs

provide opportunities for people to build from the

skills they have to the skills they need.

Avoiding assumptions about younger workers —

just like avoiding age-related stereotypes about

older workers — is crucial to ensuring that policies

and programs address the real rather than per-

ceived needs of workers and businesses.

Many jobs require industry-specific digital

skills, not just foundational skills.

Contrary to the assumption that simply acquiring

baseline, foundational skills might be sufficient for most

workers, there is robust demand for more sophisticated,

industry-specific skills. Many employers sought these

higher-level skills even for positions that required rela-

tively little education or experience.

For example, 92 percent of all jobs requiring 0-2 years

of experience required an industry-specific digital skill.

Within the subset of jobs that required a definitely

digital skill, nearly two-thirds, or 65 percent, required

applicants to have an industry-specific digital skill, either

alone or in combination with foundational digital skills.

Only 35 percent of these job postings requested founda-

tional skills alone.

29

10 CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY 11

Again, looking within the subset of jobs that required

a definitely digital skill, there were somewhat similar

trends by level of education. In this case, jobs requiring

just a high school diploma were twice as likely to require

only foundational digital skills as jobs requiring educa-

tion or training beyond high school. But even then, a

robust 43 percent of jobs requiring a high school edu-

cation demanded industry-specific skills, either alone or

in combination with foundational skills. (See Figure 3.)

Examples include job postings for warehouse workers

that require robotics skills, and ads for security officers

that require digital video skills.

Full-time jobs are more likely to require digital

skills, but part-timers still need technological

expertise.

Fully 93 percent of ads seeking full-time workers sought

people with definitely digital or likely digital skills, com-

pared to 91 percent of ads seeking part-time workers.

However, within the sub-category of job ads seeking

workers with at least one definitely digital skill, there

was a divide: Nearly half (48 percent) of ads for full-time

workers required a definitely digital skill, compared to

one-third (31 percent) of postings for part-time workers.

FIGURE 3: Many employers seek workers with industry-specific digital skills (2021)

Level of education required

Percentage of definitely

digital jobs requiring

foundational digital

skills only

Percentage of definitely

digital jobs requiring

industry-specific

digital skills only

Percentage requiring

both foundational

and industry-specific

digital skills

High school diploma/equivalent 57% 16% 27%

Associate degree 33% 28% 40%

Bachelor degree 20% 39% 41%

Master degree 24% 49% 26%

Ph.D. 19% 62% 19%

NINETY-TWO PERCENT OF ALL JOB

ADS REQUIRE DEFINITELY DIGITAL OR

LIKELY DIGITAL SKILLS. THE DEMAND IS

ROBUST ACROSS ALL INDUSTRIES, EVEN

FOR ENTRY-LEVEL JOBS.

10 CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY 11

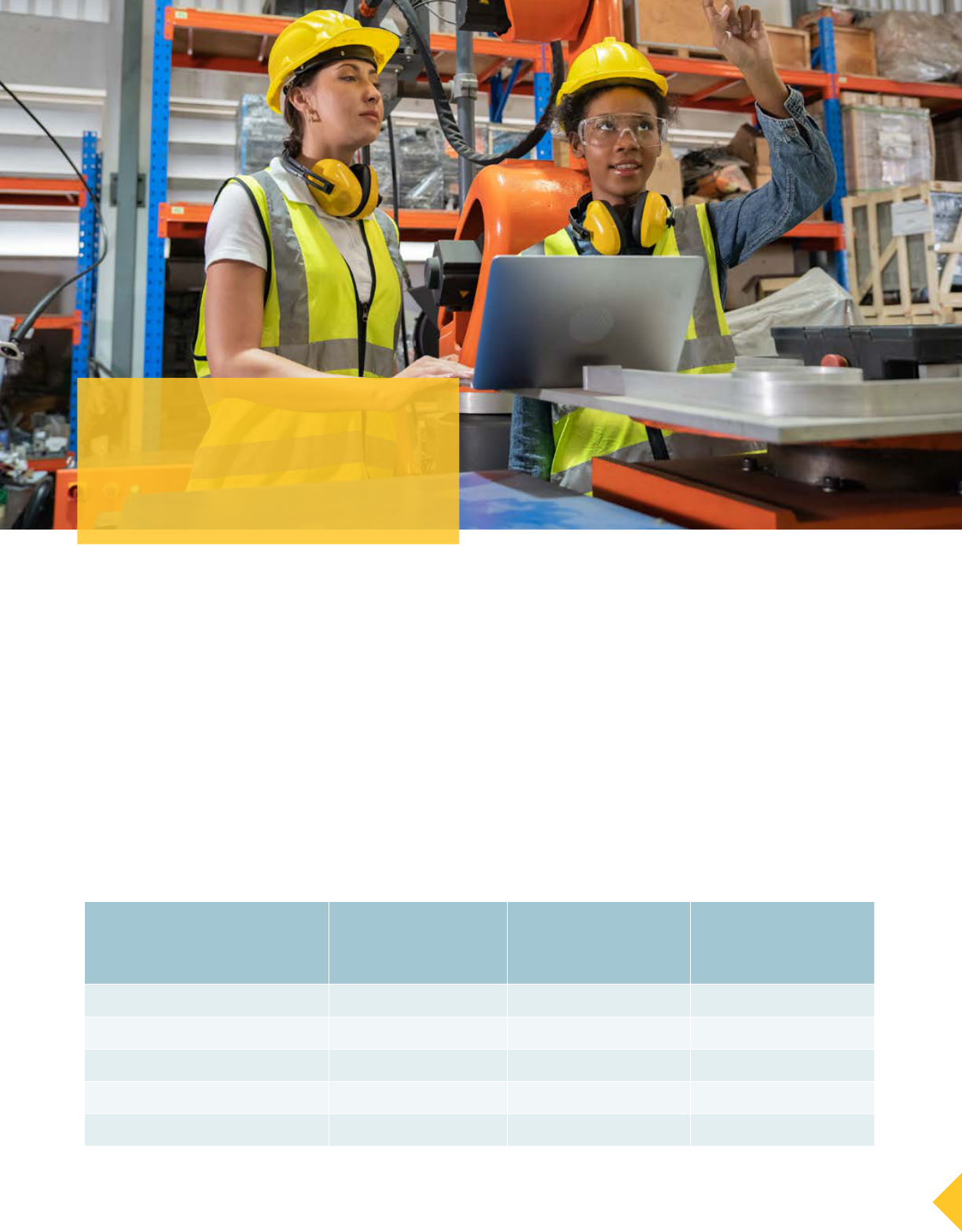

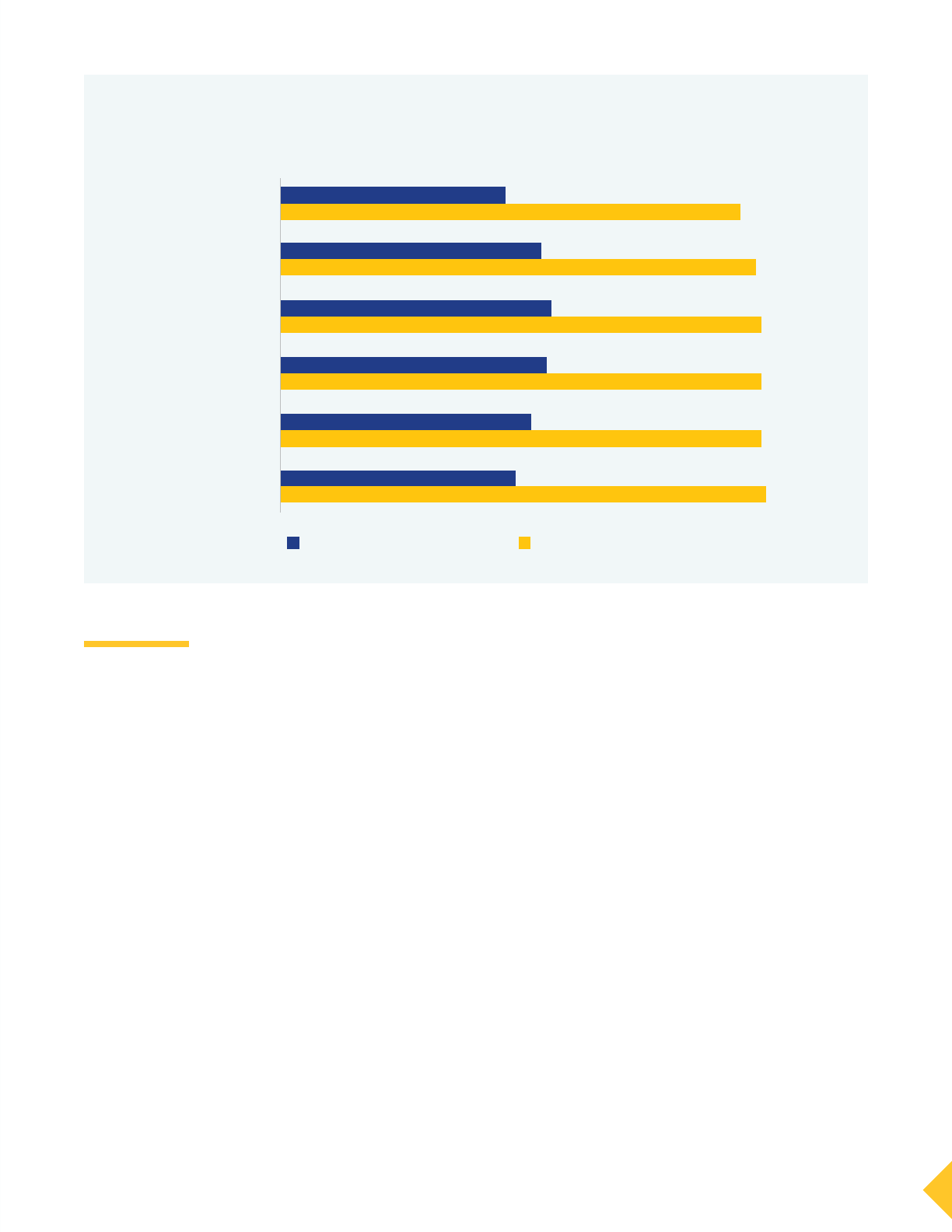

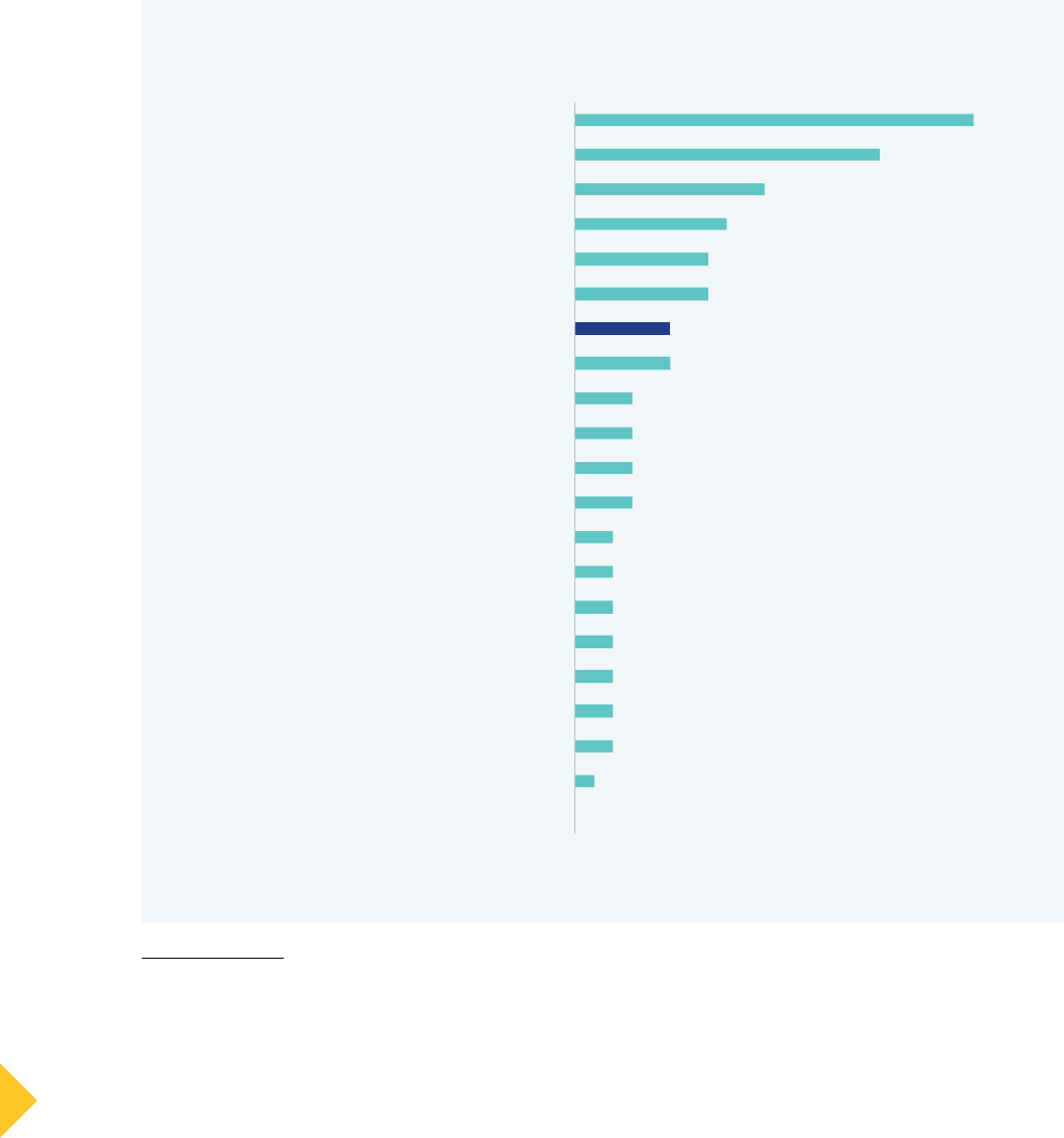

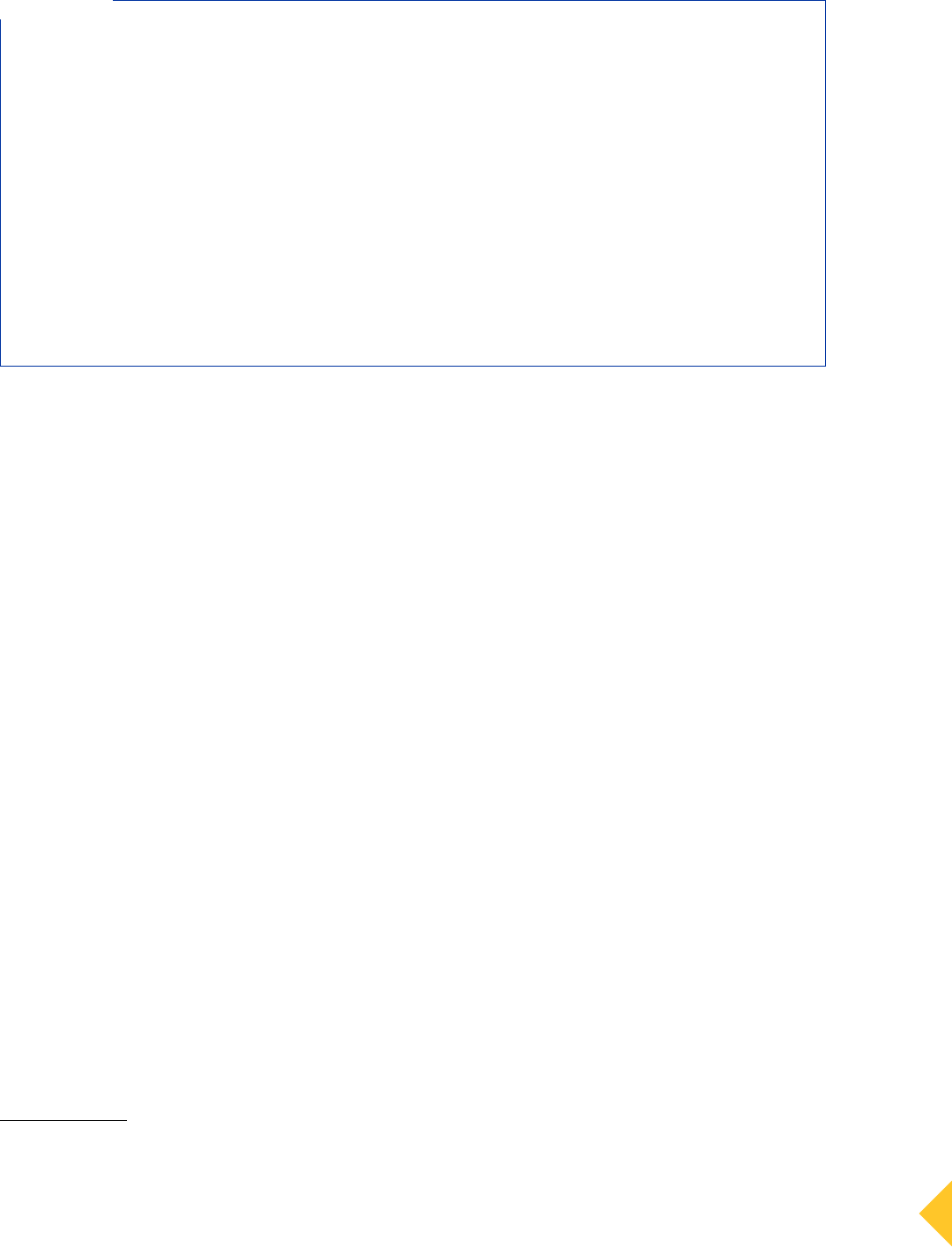

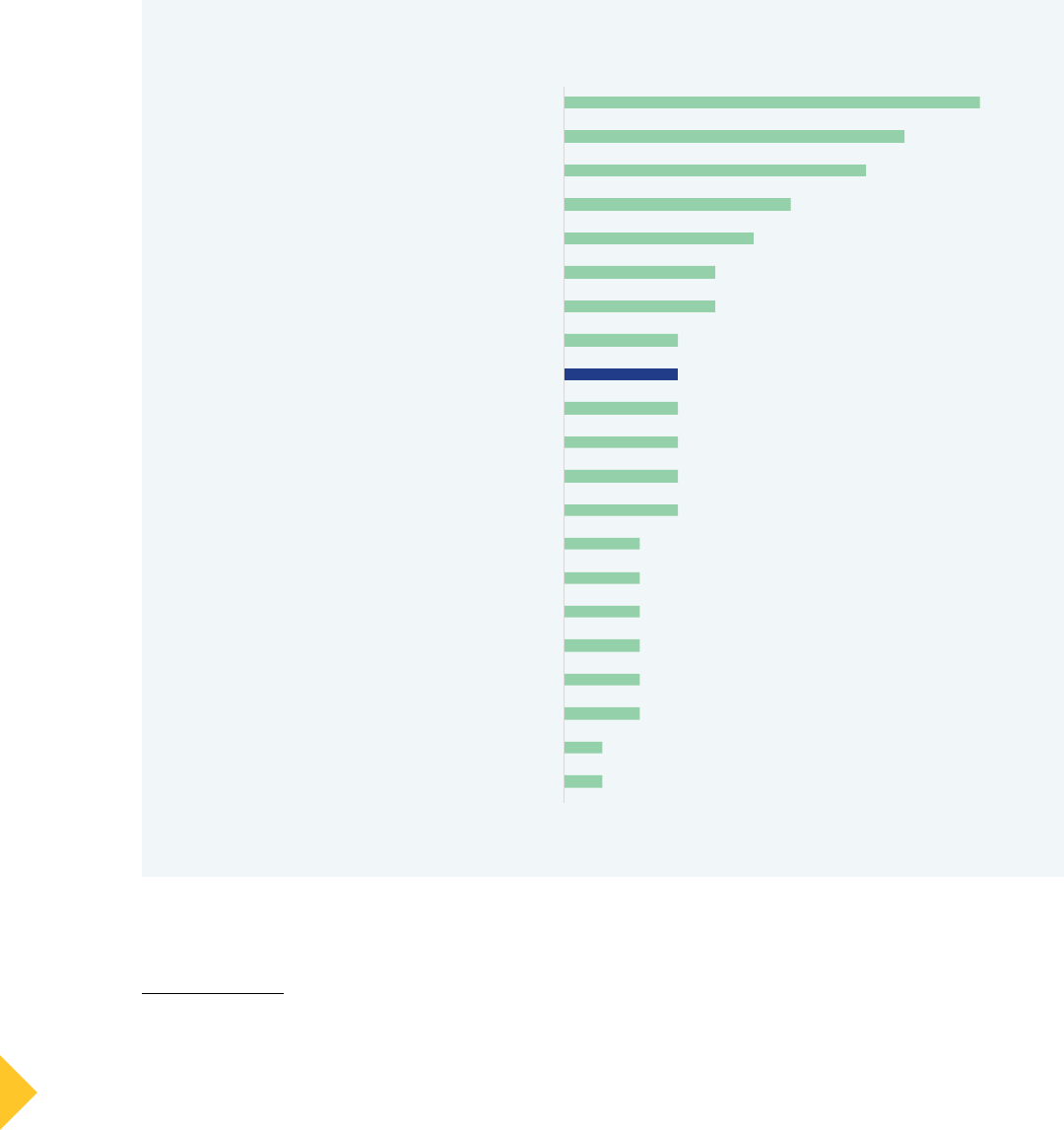

FIGURE 4: The demand for technology skills is robust across every industry (2021)

77%

73%

72%

66%

60%

56%

55%

55%

54%

49%

45%

44%

41%

39%

38%

33%

32%

32%

30%

23%

99%

98%

96%

99%

93%

96%

91%

94%

95%

89%

96%

92%

86%

91%

90%

95%

77%

95%

86%

85%

Information

Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services

Management of Companies and Enterprises

Finance and Insurance

Manufacturing

Public Administration

Utilities

Real Estate and Rental and Leasing

Wholesale Trade

Administrative and Support and

Waste Management and Remediation Services

Educational Services

Mining, Quarrying, and Oil and Gas Extraction

Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing and Hunting

Construction

Arts, Entertainment, and Recreation

Health Care and Social Assistance

Transportation and Warehousing

Retail Trade

Other Services (except Public Administration)

Accommodation and Food Services

Definitely digital skill required Likely or definitely digital skill required

12 CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY 13

NOT JUST A SILICON VALLEY PROBLEM:

THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE SPANS

EVERY INDUSTRY AND FIRM SIZE

Every industry shows strong demand for

digital skills.

A common misconception is that digital skills are pri-

marily required for information technology (IT) jobs or

are only needed for certain industries. This study found

that digital skills are widely required across the entire

range of industries in the U.S. economy.

As shown in Figure 4, the percentage of job ads requir-

ing definitely digital or likely digital skills ranges from

a low of 77 percent among the transportation and

warehousing industry sector to a high of 99 percent in

the information and finance and insurance industries.

That is, even in the industry sector at the lowest end of

the scale, fully three-quarters of job ads seek workers

with technology skills.

Even when the criteria are narrowed to include only

those job ads that require a definitely digital skill (also

shown in Figure 4), many industries still show more than

half of all job ads demanding such skills. Here there is a

wider spread between industries overall, with the high

end still the information sector at 77 percent, and the

low end now the accommodation and food services

sector at 23 percent.

30

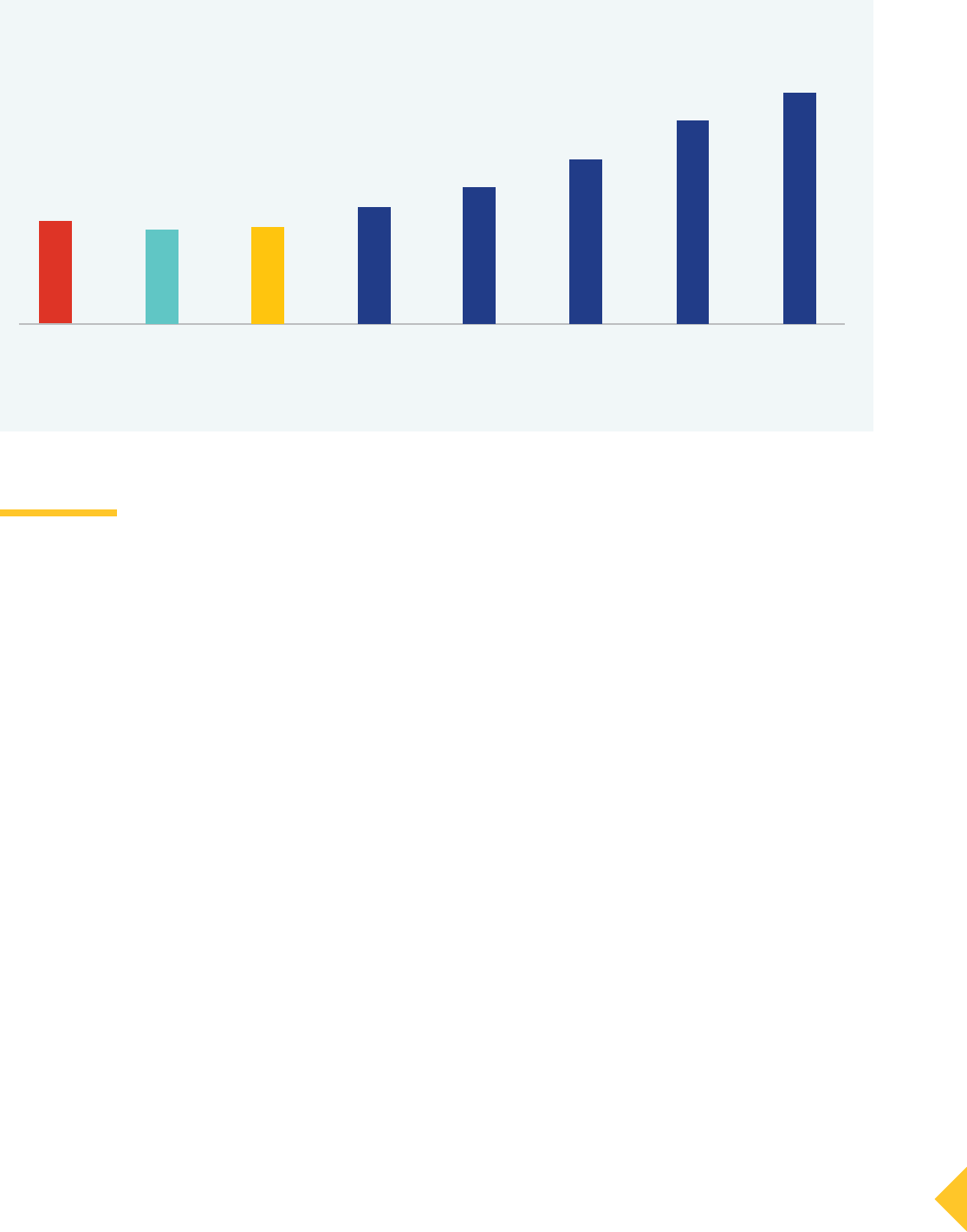

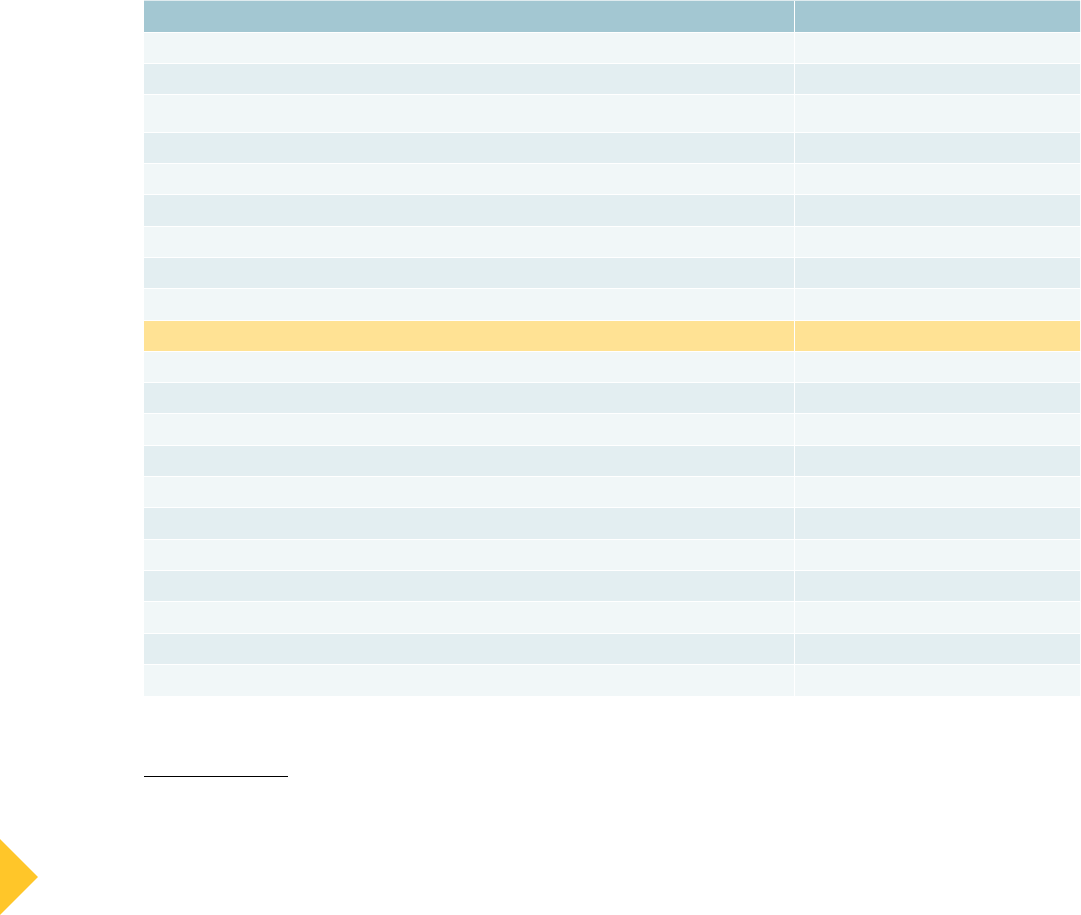

Small businesses need technologically skilled

workers too.

Smaller businesses have almost identical demand for

workers with technology skills as larger businesses.

While the dataset used for this analysis does not directly

measure the size of a company, firm size can be roughly

inferred based on the volume of job ads posted by the

company in a year.

31

Even among the smallest businesses — those that posted

between one and fifty job ads per year — 90 percent of

ads required workers to have a definitely digital or likely

digital skill. (See Figure 5.) This is consistent with earlier

research from NSC

32

that found that small businesses

were nearly as likely as large ones to need workers with

digital skills, but that smaller companies relied much

more heavily on education and workforce partners to

help upskill workers, rather than developing full-scale

in-house upskilling programs.

FIGURE 5: Small businesses are almost as likely to post job ads requiring digital skills as larger

businesses (2021)

46%

49%

52%

53%

51%

44%

95%

94%

94%

94%

93%

90%

5001+ job ads

1001-5000 job ads

501-1000 job ads

101-500 job ads

51-100 job ads

1-50 job ads

posted in 2021

Likely or definitely digital skill requiredDefinitely digital skill required

12 CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY 13

INEQUITIES WITHIN THE DIGITAL

SKILL DIVIDE

Some digitally-demanding industries employ

fewer workers of color.

The long history of occupational segregation in the

U.S. labor market means that workers of different

demographic backgrounds, particularly different

races and ethnicities, are often clustered in partic-

ular industries. Among the industries in this study

with the highest demand for workers with digital

skills (shown in Figure 4), several have a dispropor-

tionate concentration of white workers. This includes

the information industry (65 percent white) and the

finance and insurance industry (67 percent white).

33

While there are many factors behind the complex

issue of occupational segregation — such as lack of

access to quality education and training, language

barriers, structural inequities, etc. — examples such

as these are notable.

34

The relatively lower concen-

tration of workers of color in these industries sug-

gests that they are missing out on opportunities to

earn higher wages, which can worsen existing racial

inequities in income and wealth.

In occupations with many workers of color,

a changing demand for digital skills.

Although workers of color are more concentrated in

industries with slightly lower demand for digital skills,

the landscape is changing rapidly within some specific

occupations. For example, the percentage of job postings

for community health workers that required digital skills

increased by 28 percent from 2019 to 2021. Community

health workers are disproportionately likely to be Black or

Latino compared to the workforce as a whole.

35

Industries that employ people with limited education

nevertheless need workers with digital skills.

Close to half (43 percent) of workers in the manufactur-

ing industry have a high school education or less,

36

a fac-

tor that is strongly correlated with limited digital skills.

37

Yet a high percentage of job postings in manufacturing

call for workers to have definitely digital (60 percent)

or likely digital (93 percent) skills. There is a similar

phenomenon in the administrative and support and

waste management and remediation industries, where

51 percent of workers have a high school education or

less, while job postings call for workers with definitely

(49 percent) or likely (89 percent) digital skills.

A HIGH PERCENTAGE OF JOB POSTINGS IN

MANUFACTURING CALL FOR WORKERS TO

HAVE DEFINITELY DIGITAL (60 PERCENT)

OR LIKELY DIGITAL (93 PERCENT) SKILLS.

14 CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY 15

THE PAYOFF OF CLOSING THE DIGITAL

SKILL DIVIDE

Despite the high demand for digital skills and the desire

for skill-building opportunities among workers, many

people have not had the opportunity to fully develop

such skills.

38

This lack of access to digital skill training

hits workers

39

and entrepreneurs

40

of color hardest.

Increasing public investments in digital skill building

can help individual workers increase their incomes,

allow businesses to thrive, and ultimately create

positive economic spillover effects for local, state, and

national economies.

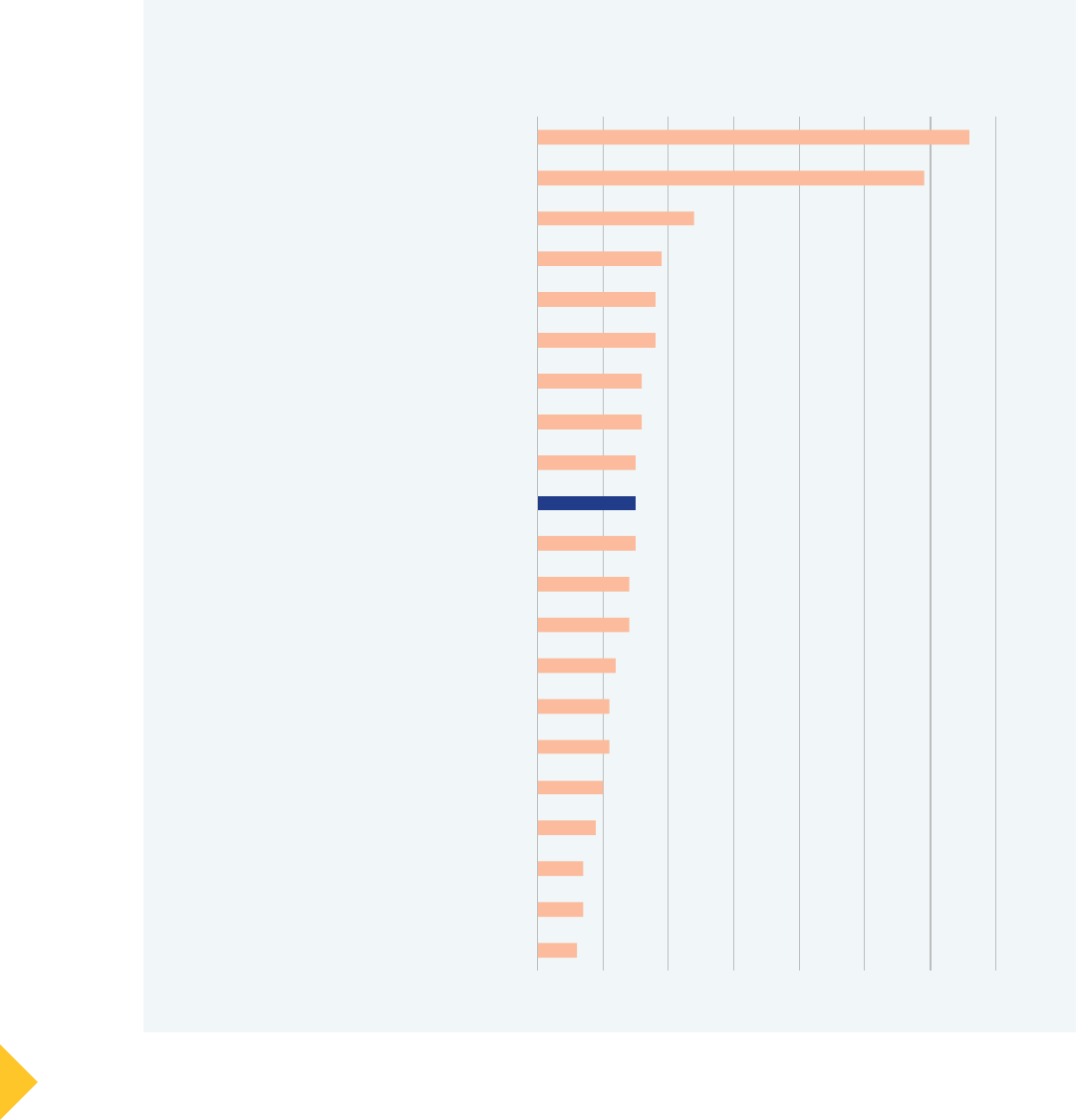

Closing the digital skill divide would catapult

more workers into economic security.

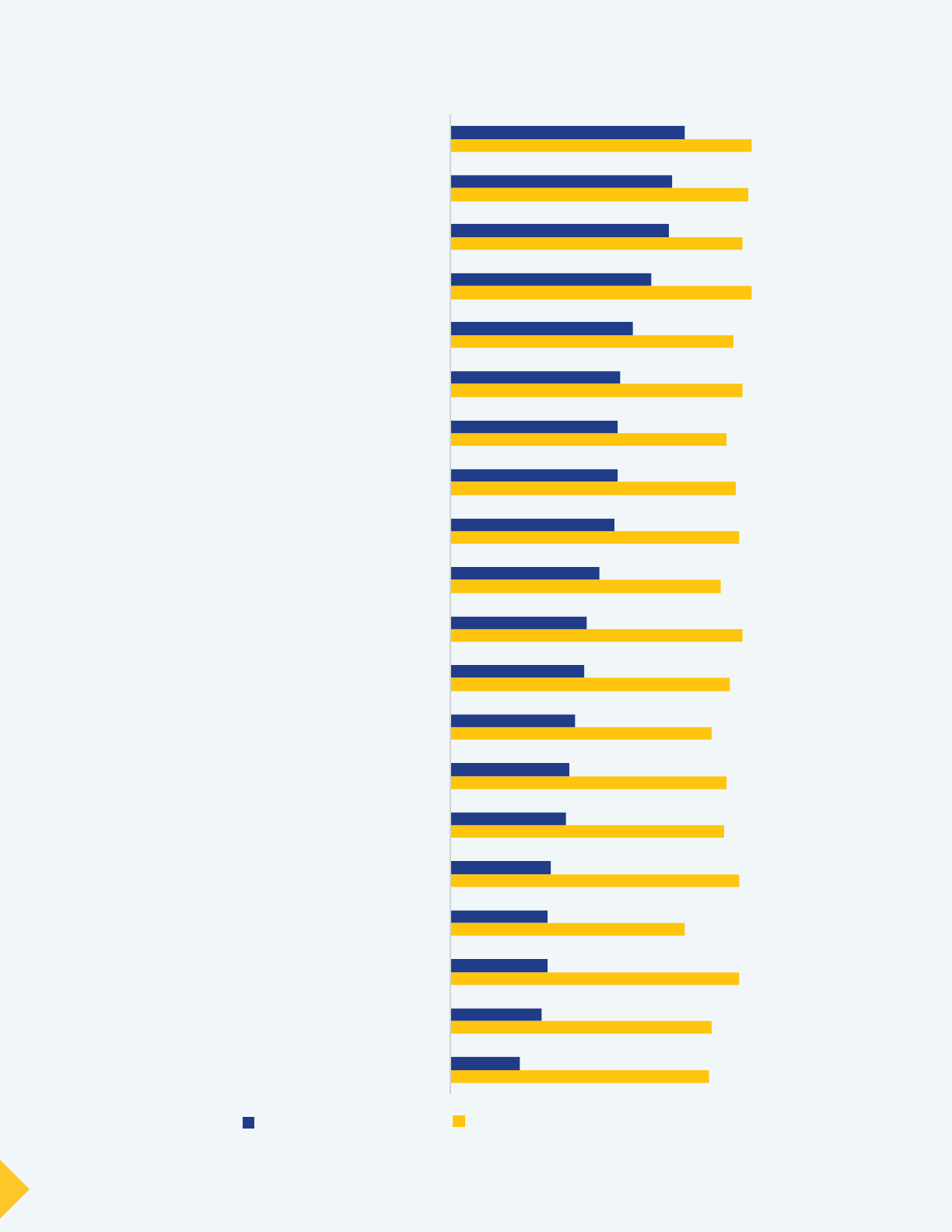

At the individual level, previous research from NSC has

clearly established that having few or no foundational

digital skills is closely correlated with lower earnings.

41

This study provides new evidence that jobs requiring

digital skills have higher median wages than jobs that do

not. Workers who have opportunities to build in-demand

digital skills could potentially increase their earnings as

they acquire new skills.

42

If a worker who was previously employed in a job that

requires zero digital skills was able to move into a job

that requires a definitely digital skill, their hourly

wage would rise by 23 percent, or more than $8,000

per year, assuming both jobs paid the median hourly

wage for their respective skill levels.

43

This economic

bump would be significant for individual workers and

their families — and would be even higher if the worker

acquired additional digital skills, as shown in Figure 6.

It is not unusual for jobs to require numerous digital

skills; nearly a quarter (22 percent, or nearly ten million)

of all job postings analyzed for this study required at

least three different digital skills. Even the highest

end — jobs requiring at least nine different digital skills —

comprised 5 percent of total job postings, or roughly

2.1 million ads.

FIGURE 6: As more digital skills are required, median hourly wage rises (2021)

$19.05

$17.62

$18.00

$21.64

$25.50

$30.58

$37.92

$43.00

Overall

(all jobs)

Job requires

no digital

skills

Job requires

only likely

digital skills

Job requires

one definitely

digital skill

Job require

three definitely

digital skills

Job requires

five definitely

digital skills

Job requires

seven definitely

digital skills

Job requires

nine definitely

digital skills

IF A WORKER WHO WAS

PREVIOUSLY EMPLOYED IN

A JOB THAT REQUIRES ZERO

DIGITAL SKILLS WAS ABLE

TO MOVE INTO A JOB THAT

REQUIRES A DEFINITELY

DIGITAL SKILL, THEIR HOURLY

WAGE WOULD RISE BY 23

PERCENT, OR MORE THAN

$8,000 PER YEAR

14 CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY 15

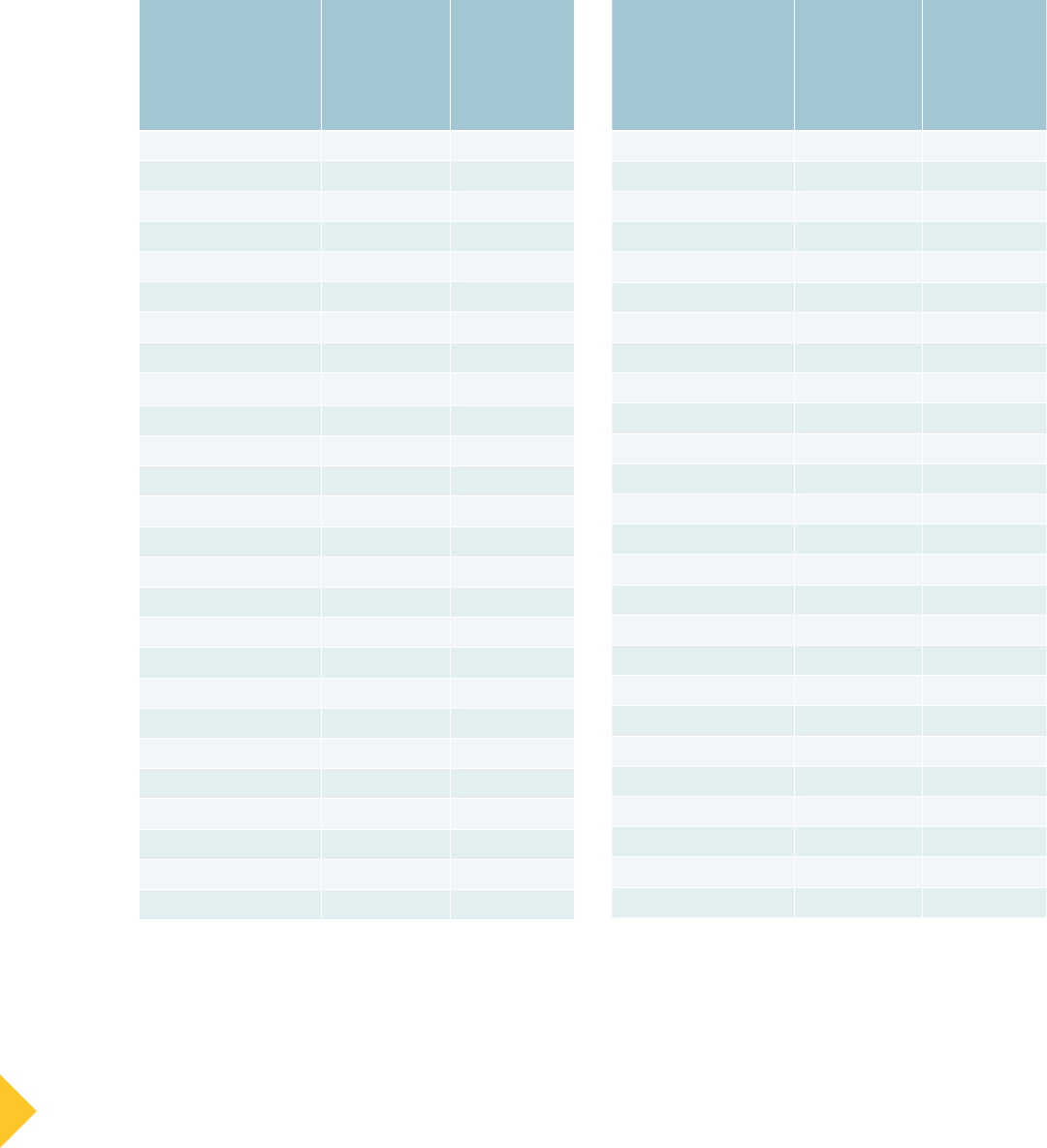

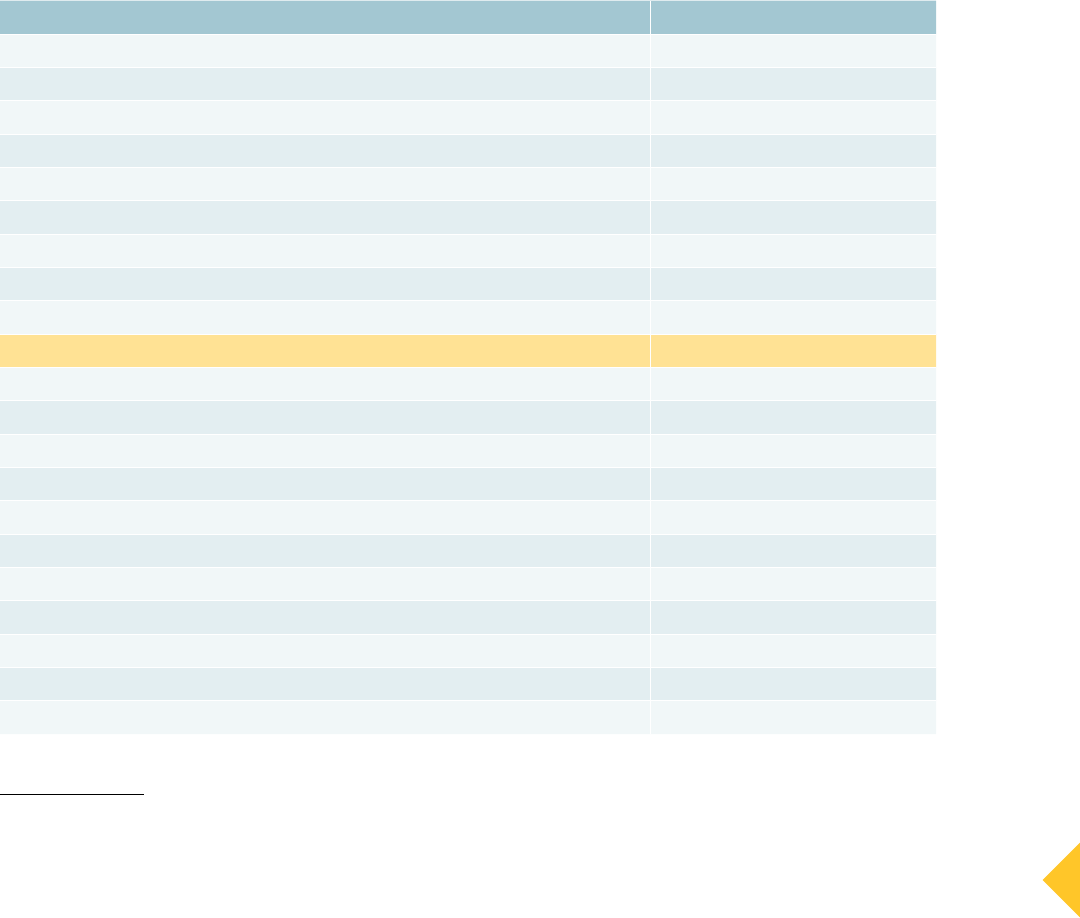

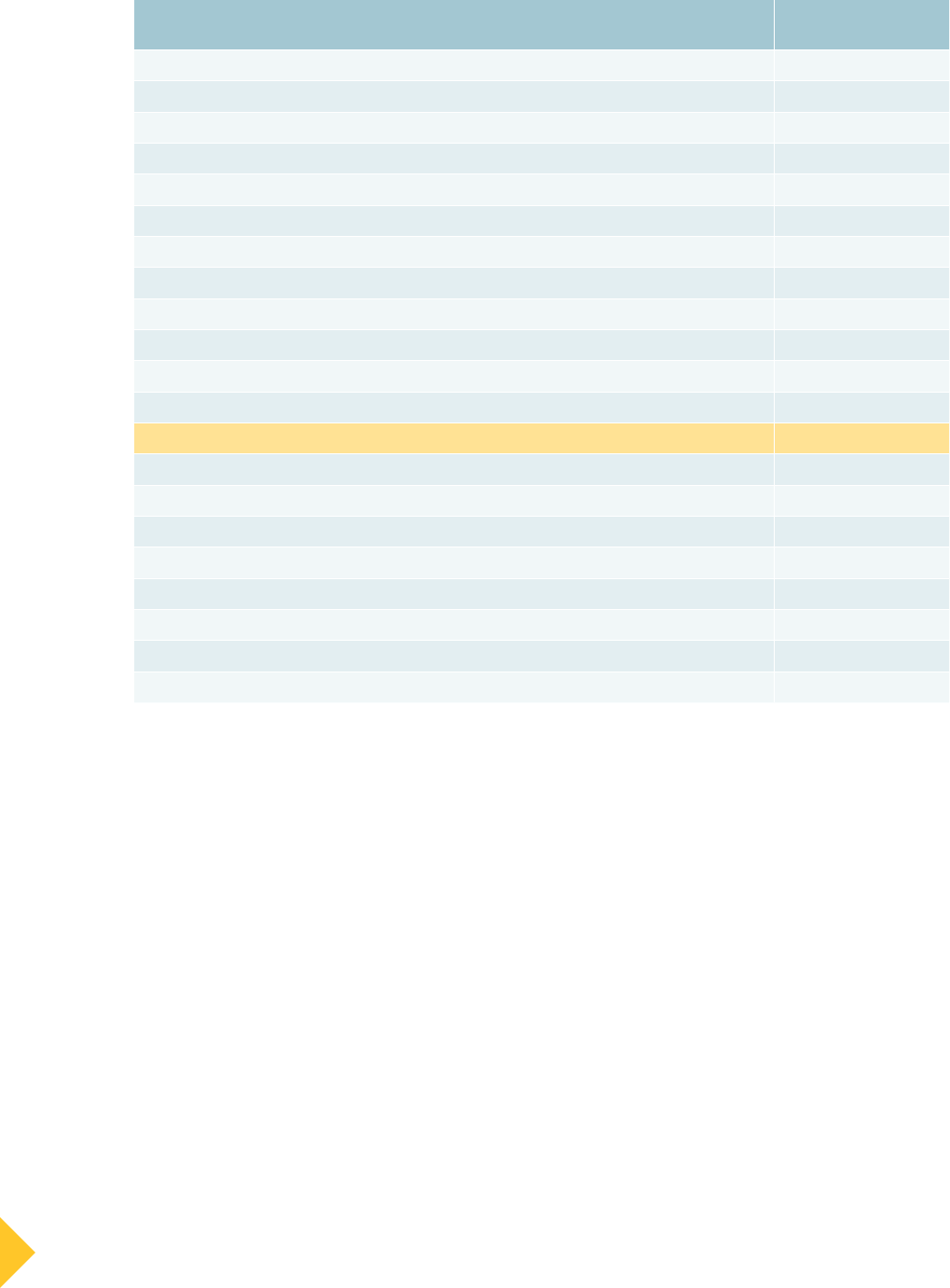

Investing in entry-level workers can help close

equity gaps.

As previously described, jobs that require no digital skills

offer substantially lower median wages than jobs that

do require such skills. Given this study’s finding that 94

percent of job ads seeking workers with a high school

diploma require digital or likely skills, as well as earlier

research documenting that workers with few or no digi-

tal skills are more likely to have low levels of education,

policymakers could prioritize upskilling these workers as

one element of closing equity gaps.

An analysis of The Census Bureau American Community

Survey data

44

shows that several of the “covered

populations” under the federal Digital Equity Act are

over-represented among workers with a high school

education or less, as shown in Figure 7. These workers

could benefit from focused investment in their digital

(and other) skills. (See Figure 7.)

Closing the digital skill divide would support

small businesses and aid business economic

vitality.

Businesses face numerous costs associated with the

digital skill divide, which could be reduced if more work-

ers had access to learning necessary skills. Specifically,

earlier research by NSC found that having a workforce

with insufficient access to digital skills functions as

an invisible drag on productivity, especially when the

people who lack digital skills are supervisors themselves,

because supervisors can serve as a bottleneck limiting

the productivity of other workers.

45

Public policy investments in workforce development and

education, such as the Digital Equity Act, are a key tactic

in addressing these challenges. Such policies are an

especially important support for small business, because

small businesses employ 47 percent of private-sector

workers,

46

and rely more heavily on publicly funded

FIGURE 7: Investing in workers with limited education could close equity gaps (2021)

13%

17%

19%

10%

11%

16%

15%

19%

16%

11%

15%

21%

13%

46%

44%

38%

20%

36%

Black

Latino

Immigrant

English learners

Persons with a disability

At or below 150% of poverty

% of all workers

age 25-64

% of workers whose highest

credential is a HS diploma

% of workers without

a HS diploma

16 CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY 17

workforce development and education partners (rather

than in-house programs) to upskill employees.

In addition, state and federal programs that support

the upskilling of incumbent workers can foster busi-

ness vitality.

47

Prior research has shown that workers

value upskilling opportunities and prefer working for

employers who offer clear, well-defined pathways to

advancement.

48

Because turnover has heavy costs for

businesses — with estimates ranging from $25,000 for

workers who quit within the first year to over $78,000

for workers who quit after five years, averting or delay-

ing turnover by ensuring that workers have upskilling

opportunities can be economically significant.

49

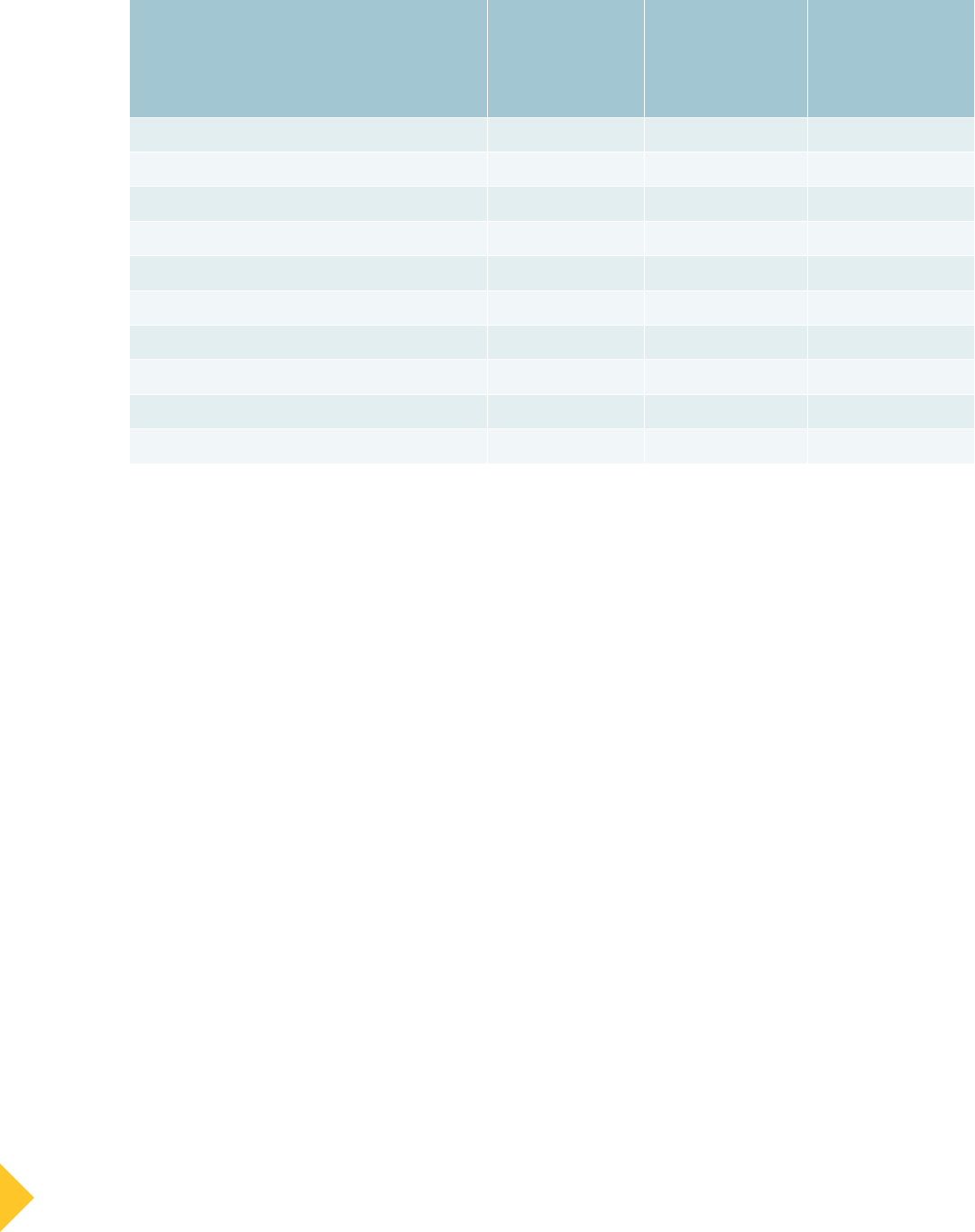

Closing the digital skill divide would create

positive spillover effects for the broader

economy.

Public investments in closing the digital skill divide

can also generate economic benefits for the broader

economy. As noted above, people who qualify for jobs

that require even one digital skill can earn an average of

$8,000 more per year than those working in jobs requir-

ing no digital skills.

50

These increased earnings could result in more state

and federal tax revenue generated by each worker.

Depending on the household size and composition, this

could range from $1,363 to $2,879 per year, as illus-

trated in Figure 8.

51

(Note: The states chosen here for

illustrative purposes, North Carolina and Illinois, are also

profiled in detail in the Appendix of this report.)

All of this increased economic activity for workers and

businesses would have additional positive spillover

effects for the communities in which they are located.

As workers earn more money, they are able to purchase

additional goods and services. As businesses increase

their revenue and profits, they are able to invest fur-

ther in expansion, pay dividends to shareholders, and

increase wages.

FIGURE 8: Increased economic impact (combined Federal and State tax revenue) generated if workers move

from a job that requires no digital skills to a job that requires one digital skill

52

Household composition

Increased economic impact:

NORTH CAROLINA

Increased economic impact:

ILLINOIS

Single Adult, No Children $1,387 per year $1,363 per year

Single Adult, One Child $2,693 per year $2,879 per year

Two Adults, No Children $2,774 per year $2,726 per year

Two Adults, Two Children $2,816 per year $2,726 per year

Note: Calculations in this table assume each working adult is earning the median hourly wage as described above, and working 40

hours per week, 50 weeks per year.

BECAUSE TURNOVER HAS HEAVY

COSTS FOR BUSINESSES — WITH

ESTIMATES RANGING FROM $25,000

TO $78,000 — AVERTING OR DELAYING

TURNOVER BY ENSURING THAT WORKERS

HAVE UPSKILLING OPPORTUNITIES CAN

BE ECONOMICALLY SIGNIFICANT.

16 CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY 17

RECOMMENDATIONS

T

he findings outlined in this report are clear and unequivocal: The labor market is moving quickly

and inexorably toward greater digital skills requirements across every industry and nearly every

occupation. At the same time, the impact of the digital skill divide disproportionately falls on some

workers, including workers of color and those without education beyond high school.

Ensuring that public investments are intentionally focused to remedy inequities facing individuals and

communities is vital to the economic success of states and the country as a whole.

53

As the federal Digital

Equity Act (part of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act passed by Congress in 2021) is imple-

mented in states, policymakers will have a powerful opportunity to close gaps in racial, gender, age and

geographic equity. Similarly, as officials work to update landmark policies such as WIOA and other work-

force and education policies, it is crucial to incorporate the latest findings on how to close the digital skill

divide.

Given the findings laid out in this report, there are three overarching recommendations to guide leaders’

decisionmaking:

A DIGITAL SKILL FOUNDATION FOR ALL.

All workers need the opportunity to develop broad-based, flexible, digital problem-solving skills for

current technologies and ongoing technological shifts.

Policymakers can support this goal by ensuring that policies targeting workers’ access to digital skills

meet workers — and the education and workforce development system — where they are. In particular,

policymakers can use federal Digital Equity Act and Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD)

funds to improve access to free or low-cost digital skills training for workers, and to ensure that workforce

development and education providers are equipped to provide high-quality upskilling services. This should

include providing high-quality professional development and technical assistance to aid workforce and

education providers in designing demand-driven digital skill-building programs.

Workforce and education advocates and providers can support this goal by speaking up for digital equity

investments that support people’s goals and aspirations, and helping policymakers connect the dots from

federal policies to specific opportunities in their own states and localities.

For example, providers may have gathered valuable data on the digital skill needs of workers and busi-

nesses that can inform policy implementation. In particular, individuals often identify “getting a job” or

“getting a better job” as their primary reason for enrolling in skill-building opportunities. Similarly, provid-

ers have often developed robust relationships with small businesses and industry sector partnerships that

can help identify opportunities to support individuals’ digital skill-building aspirations while also respond-

ing to local labor market demand.

Corporate decisionmakers and influencers can use their platforms to ensure that skills are central to

digital divide discussions in the public and policymaking spheres. The data provided in this report can help

to amplify opportunities in particular industries as well as to shift public conversation more generally to

include a skills lens.

18 CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY 19

ONGOING UPSKILLING FOR EVERY WORKER IN EVERY WORKPLACE.

Workers in every industry need the opportunity to develop industry- and occupation-specific digital

skills to adapt and advance in their careers.

Policymakers can support this goal by investing in industry sector partnerships

54

that can collaborate

with community colleges and other training providers to ensure that the talent development process is

connected to industry-specific skill needs and jobs. These partnerships can be specifically designed to

help close racial, gender, and other equity gaps

55

that have served to limit some workers’ access to jobs

that require technology skills.

Workforce and education advocates and providers can encourage policymakers to embed digital

problem-solving skills as allowable or required activities under existing workforce development, adult

education, and higher education policies, as well as digital equity

56

policies. For example, 30 states have

incumbent worker training funds that could be used to support digital skill building.

57

Corporate decisionmakers and influencers can implement policies and practices that support digital

upskilling for workers at every level of their organizations. Smaller businesses can participate in regional

industry partnerships that support these efforts across small businesses at scale.

RAPID RESKILLING FOR RAPID RE-EMPLOYMENT.

We need to be ready for sudden disruptions to the labor market or specific industries. Policies should

support rapid reskilling so workers can move from one industry to another.

Policymakers can support this goal by supporting access to skills for workers who have lost their jobs,

including those transitioning to a new industry. This includes ensuring that student financial aid policies

match the reality of how digital skills are acquired. This could entail increasing financial aid for compe-

tency-based programs. Policies could also support enrollment in high quality, short-term programs that

lead to employment and articulate to further educational pathways. These two solutions would create

meaningful on-ramps for individuals who might otherwise never pursue postsecondary credentials. It

could also include providing workers with the supports necessary to succeed in a training program — sup-

porting costs of childcare, transportation and other costs associated with job loss that can stand in the

way of someone being able to access the skill-building opportunity they need.

Workforce and education advocates and providers can support this goal by sharing their expertise with

policymakers and answering questions such as: What has your organization observed regarding digital

skill needs among staff, jobseekers, and learners? What policies have been most helpful in addressing

digital skill needs? What policies are getting in the way of addressing digital skill needs? What strategies

and tactics have been most effective in closing racial equity gaps in access to digital skills?

Influencers and corporate decisionmakers can educate state and federal policymakers about the skills

mismatches they are experiencing and the kinds of technology skills their companies need to be success-

ful, which some elected officials may not fully understand. Promoting state and federal public policies

that support the development of industry partnerships provides another avenue for employers to help

build training programs in collaboration with local community colleges and training providers.

18 CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY 19

ENDNOTES

1 The research team for this report analyzed 43 million online job

postings published in 2021 and collected by Lightcast (formerly

known as Emsi Burning Glass). Across all ads, there were 15,000

distinct skills. The research team manually coded the top 50

percent of these skills — that is, the 7,500 skills that were most

often requested in job ads. (Notably, however, this top 50 percent

accounted for 99.99% of job ads.) The team coded each skill

according to whether it was definitely digital, likely digital, or not

digital. This coding formed the basis for the original analysis and

findings in this report.

2 The team coded each skill according to whether it was definitely

digital, likely digital, or not digital. Knowledge of Salesforce

software or the Python programming language were coded as defi-

nitely digital. An example of a likely digital skill would be survey

design or bookkeeping — tasks that today are frequently accom-

plished with the use of a computer or other digital device, but could

still be carried out in an old-fashioned analog fashion. An example

of a not digital skill is changing diapers.

3 The New Landscape of Digital Literacy (National Skills Coalition,

2020.)

4 “How to improve the engagement and retention of young hourly

workers,” Kimberly Gilsdorf et al. (Harvard Business Review,

December 6, 2017.)

5 Roberts, Pasha. “The CFO and CHRO Guide to Employee Attrition.”

Workforce Solutions Review 6, no. 1 (January 2015): 8–10.

6 As detailed later in this report, in the Lightcast dataset used for this

analysis, jobs that require no digital skills had an average median

hourly wage of $17.62, compared to $21.64 for jobs that require one

definitely digital skill.

7 Feenberg, Daniel Richard, and Elizabeth Coutts, An Introduction

to the TAXSIM Model, Journal of Policy Analysis and Management

vol 12 no 1, Winter 1993, pages 189-194. Shane Orr (2022). usincom-

etaxes: Calculate Federal and State Income Taxes in the United

States. R package version 0.5.4. https://cran.r-project.org/

package=usincometaxes

8 Learn more about the Digital Equity Act’s covered populations via

the U.S. Commerce Department’s official InternetForAll.gov site,

and NSC’s fact sheet.

9 The Roadmap to Racial Equity: An Imperative for Workforce

Development Advocates. (National Skills Coalition, 2019.)

10 Learn more about industry sector partnerships in the Sector

Partnerships Policy Toolkit (National Skills Coalition, 2015) and on

the NSC website.

11 For example, see Expanding Digital Inclusion via the Bipartisan

Infrastructure Law (National Skills Coalition, 2022.)

12 Applying a Racial Equity Lens to Digital Literacy (National Skills

Coalition, 2020.)

13 This definition builds on the definition of the digital divide used

by the nonprofit National Digital Inclusion Alliance, viewable at:

https://www.digitalinclusion.org/definitions/

14 The nonprofit Digital US coalition defines digital resilience as:

“having the awareness, skills, agility, and confidence to be empow-

ered users of new technologies and adapt to changing digital skill

demands. Digital resilience improves capacity to problem-solve and

upskill, navigate digital transformations, and be active participants

in society and the economy.”

15 The New Landscape of Digital Literacy (National Skills Coalition,

2020.)

16 Examples of such inequities include digital redlining that limits

the availability of high-speed internet in some communities;

under-funded educational institutions that are unable to provide

their students with robust digital technologies for learning; and

barriers to access that limit students’ and workers’ ability to

build digital skills and businesses’ ability to advance into the dig-

ital age. In addition, limited income and limited access to capital

handicaps digital access and skill-building opportunities, often

exacerbated by the wealth gap and disproportionately affecting

workers and entrepreneurs of color.

17 For more on the role of public policy in remedying inequities, see

The Roadmap to Racial Equity: An Imperative for Workforce

Development Advocates (National Skills Coalition, 2019.)

18 The New Landscape of Digital Literacy (National Skills Coalition,

2020.)

19 Frequently Asked Questions (U.S. Small Business Administration,

October 2020.)

20 “How to improve the engagement and retention of young hourly

workers,” Kimberly Gilsdorf et al. (Harvard Business Review,

December 6, 2017.)

21 Roberts, Pasha. “The CFO and CHRO Guide to Employee

Attrition.” Workforce Solutions Review 6, no. 1 (January 2015):

8–10.

22 As detailed later in this report, in the Lightcast dataset used for

this analysis, jobs that require no digital skills had an average

median hourly wage of $17.62, compared to $21.64 for jobs that

require one definitely digital skill.

23 Feenberg, Daniel Richard, and Elizabeth Coutts, An Introduction

to the TAXSIM Model, Journal of Policy Analysis and Management

vol 12 no 1, Winter 1993, pages 189-194. Shane Orr (2022).

usincometaxes: Calculate Federal and State Income Taxes in the

United States. R package version 0.5.4. https://cran.r-project.org/

package=usincometaxes

24 Learn more about the Digital Equity Act’s covered populations via

the U.S. Commerce Department’s official InternetForAll.gov site,

and NSC’s fact sheet.

25 For a full listing of state demand for digital skills, see the

Appendix.

26 The Lightcast dataset used for this report also includes some

job postings that required workers to have zero to two years of

experience in a particular role; those workers might not be new

entrants to the workforce at large.

27 Note for this figure: Data refers to the subset of 24 million job ads

(out of the total 43 million in this study) for which Lightcast was

able to discern an educational level.

28 The New Landscape of Digital Literacy (National Skills Coalition,

2020.)

29 It is unclear from this dataset whether higher-level jobs are genu-

inely less likely to require foundational skills, or simply less likely

to spell them out in their job descriptions. Preliminary indications

from qualitative interviews suggest that employers may assume

that workers with greater education have acquired basic digital

competence — even if that assumption is not always borne out in

reality — and thus do not bother to spell out the requirement in a

job description.

20 CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY 21

30 Qualitative interviews conducted by NSC suggest that part of the

story here is that smaller and more economically fragile businesses

are slower to digitize, meaning that their ‘likely digital’ tasks (such

as order processing or inventory management) may still be manual

or analog, while larger and better-resourced businesses have

already moved those functions to software systems.

31 Notably, this is only an approximate measure, because there is

substantial variation in the “churn” rate of turnover across different

companies and industries, and thus the volume of job postings that

might be posted in a given time period.

32 Boosting Digital Literacy in the Workplace (National Skills

Coalition, 2020.)

33 Demographic data throughout this section comes from the U.S.

Census Bureau American Community Survey 5-year estimates

(2016-2020.)

34 For example, see: The Evolution of Occupational Segregation in

the United States, 1940–2010: Gains and Losses of Gender–Race/

Ethnicity Groups (Demography, 2015); The extent of occupational

segregation in the US: Differences by race, ethnicity, and gender

(Society for the Study of Economic Inequity, 2010); and Racism

and the Economy: Focus on Employment (Federal Reserve Bank of

Atlanta, 2020.)

35 Community Health Worker National Workforce Survey (U.S.

Department of Health and Human Services, 2007.)

36 Demographic data comes from the U.S. Census Bureau American

Community Survey 5-year estimates (2016-2020.)

37 The New Landscape of Digital Literacy (National Skills Coalition,

2020.)

38 Applying a Racial Equity Lens to Digital Literacy (National Skills

Coalition, 2020.)

39 Multiple factors combine to create these challenges. For example,

Black and Latino workers are less likely to have bachelor’s degrees,

and employers invest 58 percent of their upskilling dollars in work-

ers at that educational level, compared to just 17 percent of training

dollars provided to workers with high school diplomas or less. See

Training: The Role of Employer-Provided Training in the American

Postsecondary Education and Training System (Georgetown

University Center on Education and the Workforce, 2015). For

more on related issues, see Applying a Racial Equity Lens to

Digital Literacy (National Skills Coalition, 2020) and The Roadmap

to Racial Equity: An Imperative for Workforce Development

Advocates (National Skills Coalition, 2019.)

40 For an example of the disproportionate headwinds faced by entre-

preneurs of color, see: “Which small businesses are most vulnera-

ble to COVID-19—and when” (McKinsey & Company, June 18, 2020.)

41 Earlier research conducted by National Skills Coalition (The New

Landscape of Digital Literacy, 2020) found that fully 31 percent

of employed U.S. adults had few or no foundational digital skills.

Workers without digital skills had lower incomes and less formal

education compared to peers with stronger digital skills. Because

this data was drawn from the Survey of Adult Skills (also known

as the PIAAC), it reflects a direct, actual test of workers’ skills, not

merely a self-reported survey or other indirect measure. Additional

informal research conducted since the pandemic — including qual-

itative interviews with employers as well as direct assessment of

incumbent workers using the Northstar Digital Literacy Assessment

— indicates that the 31 percent number may even be conservative.

Workers reported spending significant time and effort covering for

and compensating for their digital skill gaps.

42 It is important to note that correlation is not causation. Simply

acquiring a digital skill is not a guarantee that a worker will be able

to move into a better-paying job. However, research indicates that

in general, workers with greater skills are indeed able to command

more opportunities in the labor market. In addition, earlier research

has shown that the U.S. generally has stronger returns to foun-

dational skills than other developed countries. Returns to Skills

Around the World: Evidence from the PIAAC. (Hoover Institution,

2013.)

43 Median wage of $17.62 an hour for jobs with no digital skills com-

pared to $21.64 an hour for jobs requiring a definitely digital skill.

Calculation assumes full-time, year-round employment of 40 hours

a week, 50 weeks a year.

44 All data in this section comes from the American Community

Survey 2016-2020 five-year estimates.

45 NSC’s research found that between one-fifth and one-third of

people with few or no foundational digital skills are nevertheless

supervising other workers. See: The New Landscape of Digital

Literacy (National Skills Coalition, 2020.)

46 Frequently Asked Questions (U.S. Small Business Administration,

October 2020.)

47 Funding Resilience (National Skills Coalition, 2021.)

48 “How to improve the engagement and retention of young hourly

workers,” Kimberly Gilsdorf et al. (Harvard Business Review,

December 6, 2017.)

49 Roberts, Pasha. “The CFO and CHRO Guide to Employee Attrition.”

Workforce Solutions Review 6, no. 1 (January 2015): 8–10.

50 In the Lightcast dataset used for this analysis, jobs that require no

digital skills had an average median hourly wage of $17.62, com-

pared to $21.64 for jobs that require one definitely digital skill.

51 Feenberg, Daniel Richard, and Elizabeth Coutts, An Introduction

to the TAXSIM Model, Journal of Policy Analysis and Management

vol 12 no 1, Winter 1993, pages 189-194. Shane Orr (2022). usincom-

etaxes: Calculate Federal and State Income Taxes in the United

States. R package version 0.5.4. https://cran.r-project.org/

package=usincometaxes

52 Ibid. Note also: Tax liabilities are estimated based on rule year 2022.

Federal tax liabilities represent total taxes minus applicable tax

credits for a household (Child Tax Credit and Earned Income Tax

Credit).

53 The Roadmap to Racial Equity: An Imperative for Workforce

Development Advocates (National Skills Coalition, 2019.)

54 Learn more about industry sector partnerships in the Sector

Partnerships Policy Toolkit (National Skills Coalition, 2015) and on

the NSC website.

55 The Roadmap to Racial Equity: An Imperative for Workforce

Development Advocates (National Skills Coalition, 2019.)

56 For example, see, Expanding Digital Inclusion via the Bipartisan

Infrastructure Law (National Skills Coalition, 2022.)

57 Funding Resilience (National Skills Coalition, 2021.)

20 CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY 21

22 CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY 23

OVERVIEW

The national data presented in this report has powerful implications for state officials and workforce and

education advocates. In this appendix, NSC and the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta have included two charts

that illustrate the demand for digital skills by state, using the same Lightcast data set that was used in our

full report.

However, because the fifty states vary significantly in factors such as the economic mix of their industries

and the demographic makeup of their workforce, state stakeholders may find it helpful to juxtapose these

national findings with additional, more state-specific analysis.

State leaders have a wealth of resources they can call upon to carry out such analyses, including Labor

Market Information (LMI) agencies, labor departments, and state workforce development boards. Nonprofit

policy advocacy organizations, universities, and research institutes may also have expertise and interest in

conducting such analyses.

To illustrate how states might go about this, NSC and the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta have collaborated

to produce sample profiles for two states — North Carolina and Illinois — that are included in this appendix.

These state profiles can serve multiple purposes. In particular, they can:

■

Help states identify where to target digital skill-building investments. The bipartisan infrastructure

law passed by Congress in 2021 included major new investments for states via the Digital Equity Act,

which provides $2.75 billion in federal funding to support digital inclusion programs. As states develop the

required Digital Equity Plans that will form the roadmap for these investments, this data can help inform

their efforts.

■

Help states identify where more information or research is needed. State leaders can use this data as

a starting point for discovering more about particular industries’ need for technologically skilled workers,

and how they might target upskilling resources to remedy inequities among demographic groups.

GUIDING QUESTIONS FOR STATES TO CONSIDER

As states are analyzing this data to address digital skills needs and implement new digital equity investments,

there are some questions that can help to frame their analysis. In particular, policymakers and advocates

may wish to consider:

■

What particular barriers do specific demographic groups of workers (including those defined as “covered

populations” in the Digital Equity Act) face in your state?

■

How might investments inadvertently exacerbate inequities facing these workers? How might investments

be better targeted to avoid worsening (and instead to improve) inequities?

■

What non-public data on digital access or skills are available to inform state decision making? (For exam-

ple, does the state collect information on whether Unemployment Insurance claimants access the system

via telephone versus the internet?)

■

How can this data be leveraged to better illuminate challenges and opportunities?

APPENDIX:

SELECTED STATE PROFILES

22 CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY CLOSING THE DIGITAL SKILL DIVIDE: THE PAYOFF FOR WORKERS, BUSINESS, AND THE ECONOMY 23

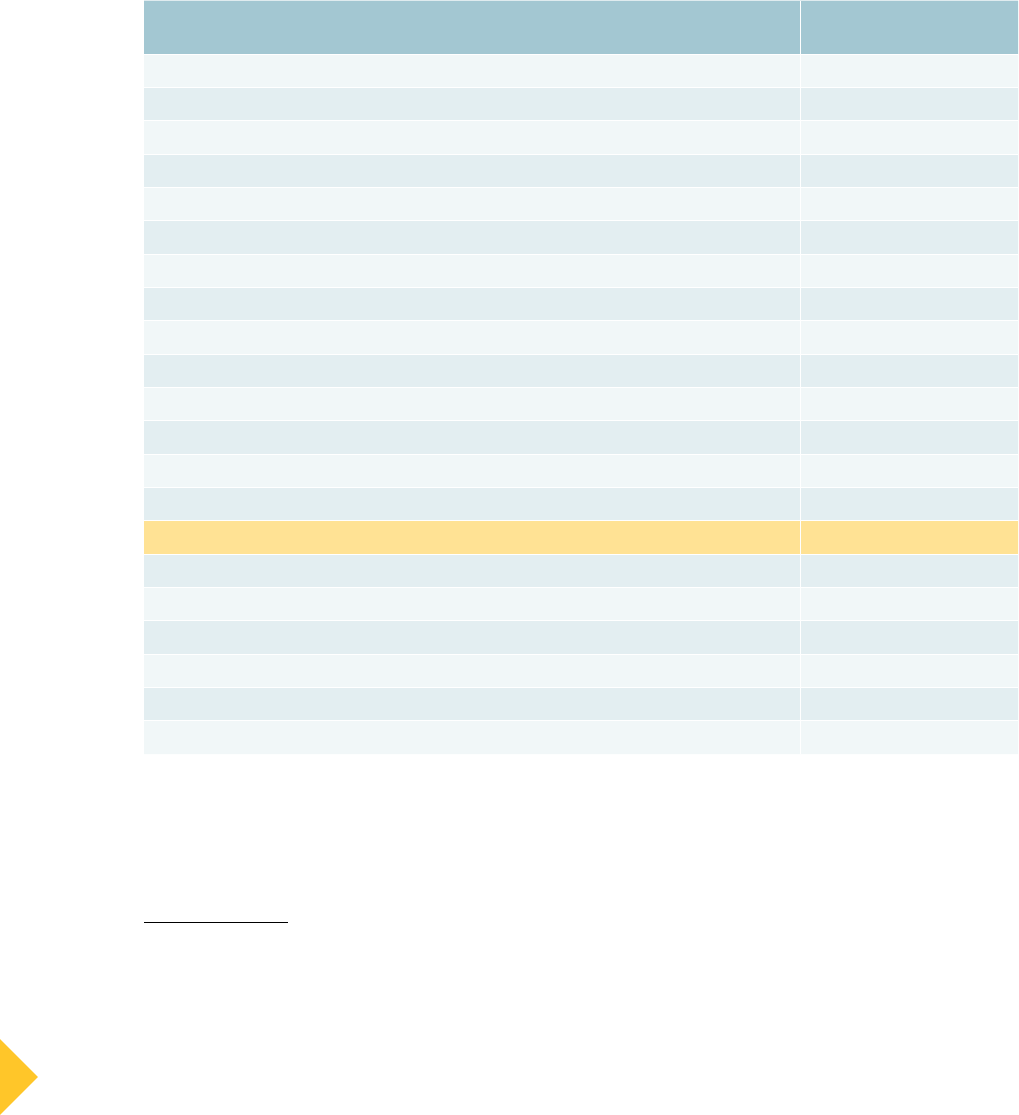

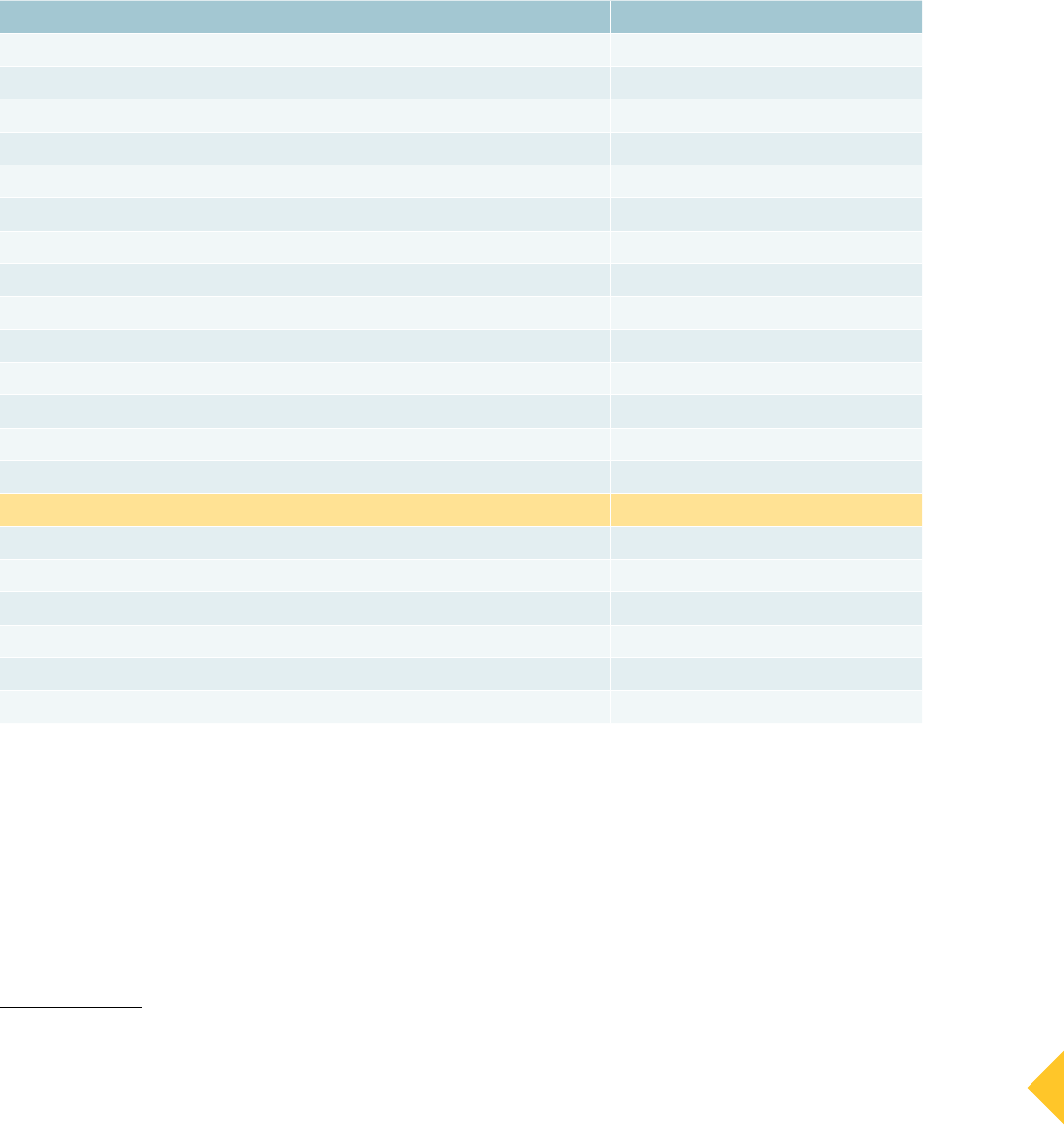

DIGITAL SKILL DEMANDS ACROSS STATES

The demand for digital skills varies somewhat by state. As illustrated in Figure 1, job postings across all states

and territories show high demand for workers with likely digital skills, ranging from Montana at 88 percent

to the District of Columbia at 95 percent. There are greater differences among the subset of job postings

requiring a definitely digital skill, from a low of 39 percent of job postings in Indiana to a high of 66 percent

in D.C.

FIGURE 1: Demand for digital skills by state/territory, by percent of jobs requiring a likely digital skill

State/Territory

Percent of

job postings

including a

likely digital

skill

Percent of

job postings

including a

definitely

digital skill

District of Columbia 95% 66%

Puerto Rico 94% 53%

Hawaii 93% 47%

Alaska 93% 47%

Massachusetts 92% 51%

Maryland 92% 51%

Wyoming 92% 47%

New York 92% 52%

Virginia 92% 53%

New Mexico 92% 45%

Connecticut 91% 46%

Washington 91% 49%

California 91% 51%

Texas 91% 49%

Delaware 91% 48%

Utah 91% 51%

Colorado 91% 47%

West Virginia 91% 42%

Arizona 91% 47%

South Dakota 91% 42%

North Dakota 91% 44%

North Carolina 91% 46%

South Carolina 91% 42%

Minnesota 91% 48%

Louisiana 90% 41%

New Hampshire 90% 43%

State/Territory

Percent of

job postings

including a

likely digital